Master’s Thesis, MIT SM.Arch.S Architecture & Urbanism

The Slow Zone: Alternative Paths for Bali

Abstract

On the surface, Bali’s narrative is one of dualism between

rural and urban, traditional and modern, local and foreign. However, flows of

commodity and patterns of human migration reveal that these dichotomies are

irrelevant, as all coexist in different intensities to balance its two main

economies: agriculture and tourism. The inability to recognize this

interdependence has resulted in development projects that are harmful for both

sectors. The Slow Zone is an alternative model of development that favors and

engages local growth instead of relying on outside actors devoid of context.

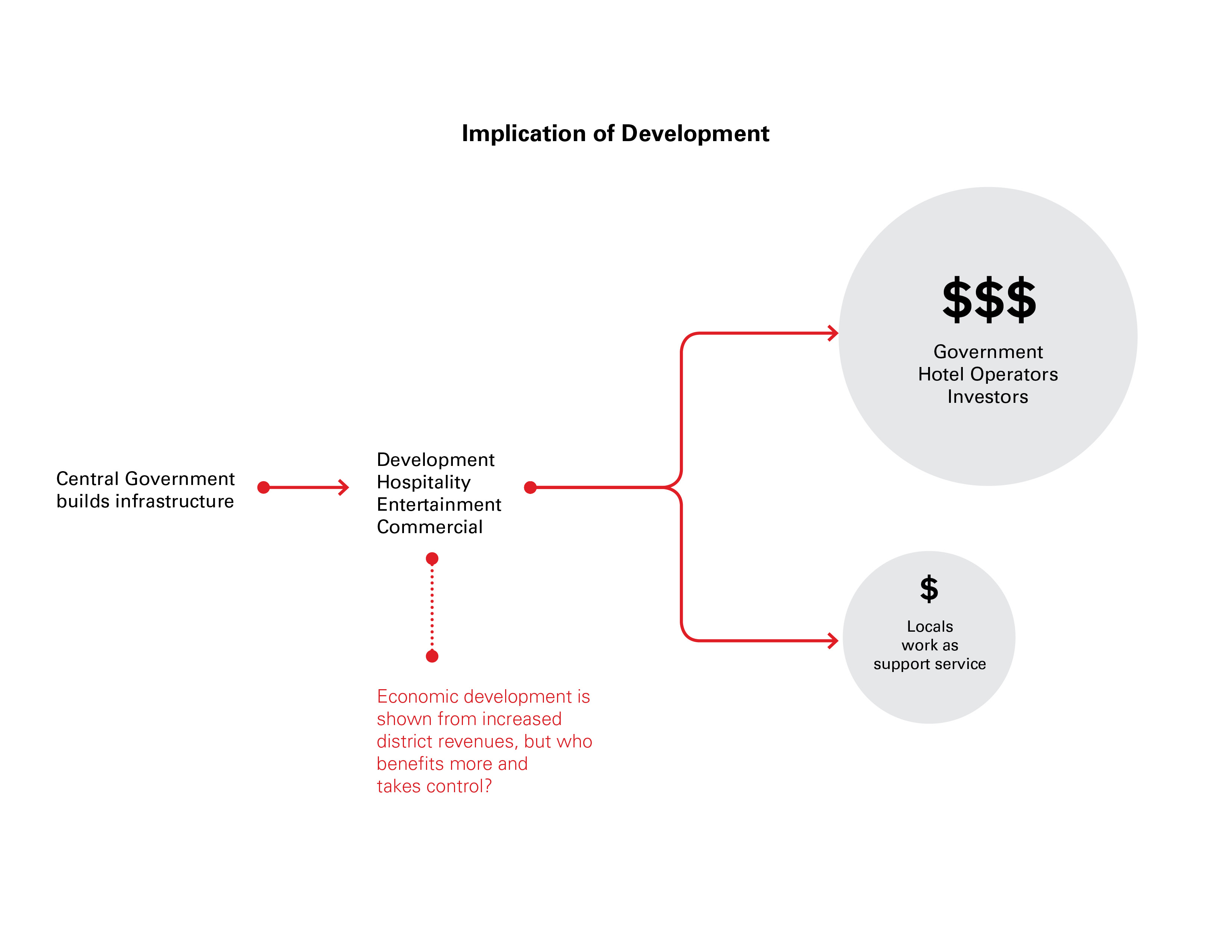

Following the 1997 Asia Financial Crisis, fiscal decentralization in Indonesia distributed administrative power from the province to the district level, creating competition among districts. The high profitability of real estate over agricultural land created development schemes that favor outside capital instead of local needs.

Following the 1997 Asia Financial Crisis, fiscal decentralization in Indonesia distributed administrative power from the province to the district level, creating competition among districts. The high profitability of real estate over agricultural land created development schemes that favor outside capital instead of local needs.

The 2014 Village Law is a

decentralization

mechanism that provides direct funding for

infrastructural

development and village-owned enterprises based on each village’s human and

natural resource.

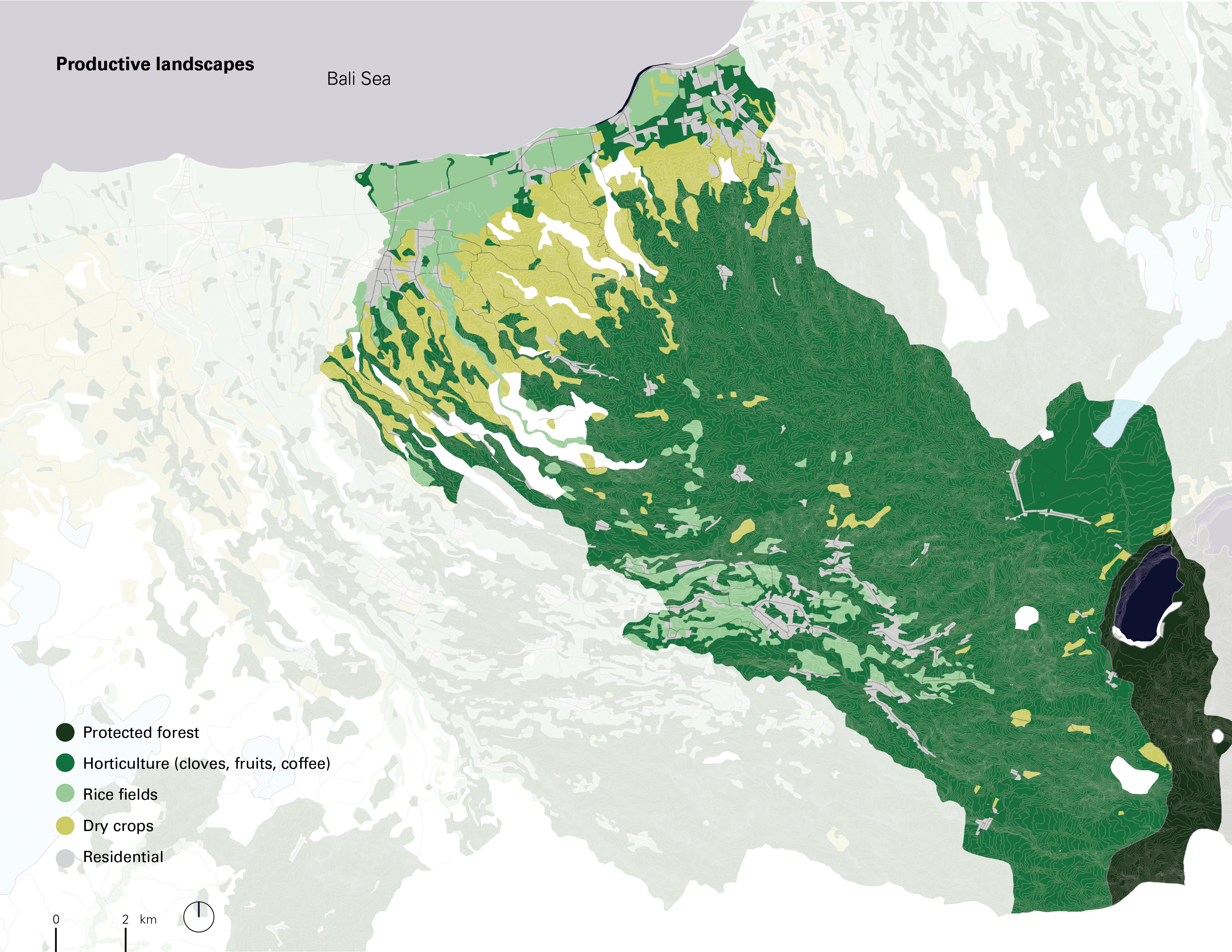

The Slow Zone proposes reterritorialization of village networks based on agriculture and social relationships. The project site in North Bali represents a broad range of agricultural diversity, which become the foundation for the development schemes. Three design proposals: a mixed-use development, an inter-village cooperative, and an institution, each respectively located in the lowland, midland, and highland areas, respond to the political history, cultural richness, and geographical challenges of the local context. The goal of the spatial design strategies is to retain local control of land and economy through coupling, and not separation of, tourism and agriculture.

Click to read full thesis book.

The Slow Zone proposes reterritorialization of village networks based on agriculture and social relationships. The project site in North Bali represents a broad range of agricultural diversity, which become the foundation for the development schemes. Three design proposals: a mixed-use development, an inter-village cooperative, and an institution, each respectively located in the lowland, midland, and highland areas, respond to the political history, cultural richness, and geographical challenges of the local context. The goal of the spatial design strategies is to retain local control of land and economy through coupling, and not separation of, tourism and agriculture.

Click to read full thesis book.

Project:

Thesis. Master of Science in Architecture Studies, Architecture & Urbanism Concentration.

MIT School of Architecture and Planning.

Completion:

June 2018

Thesis Committee:

Advisors: Adele Santos & Rafi Segal (MIT SA+P). Readers: Sai Balakrishnan (Harvard GSD) & Daliana Suryawinata (SHAU Indonesia).

Thesis. Master of Science in Architecture Studies, Architecture & Urbanism Concentration.

MIT School of Architecture and Planning.

Completion:

June 2018

Thesis Committee:

Advisors: Adele Santos & Rafi Segal (MIT SA+P). Readers: Sai Balakrishnan (Harvard GSD) & Daliana Suryawinata (SHAU Indonesia).

Part I: Fieldwork

Capturing the senses:

a visual diary

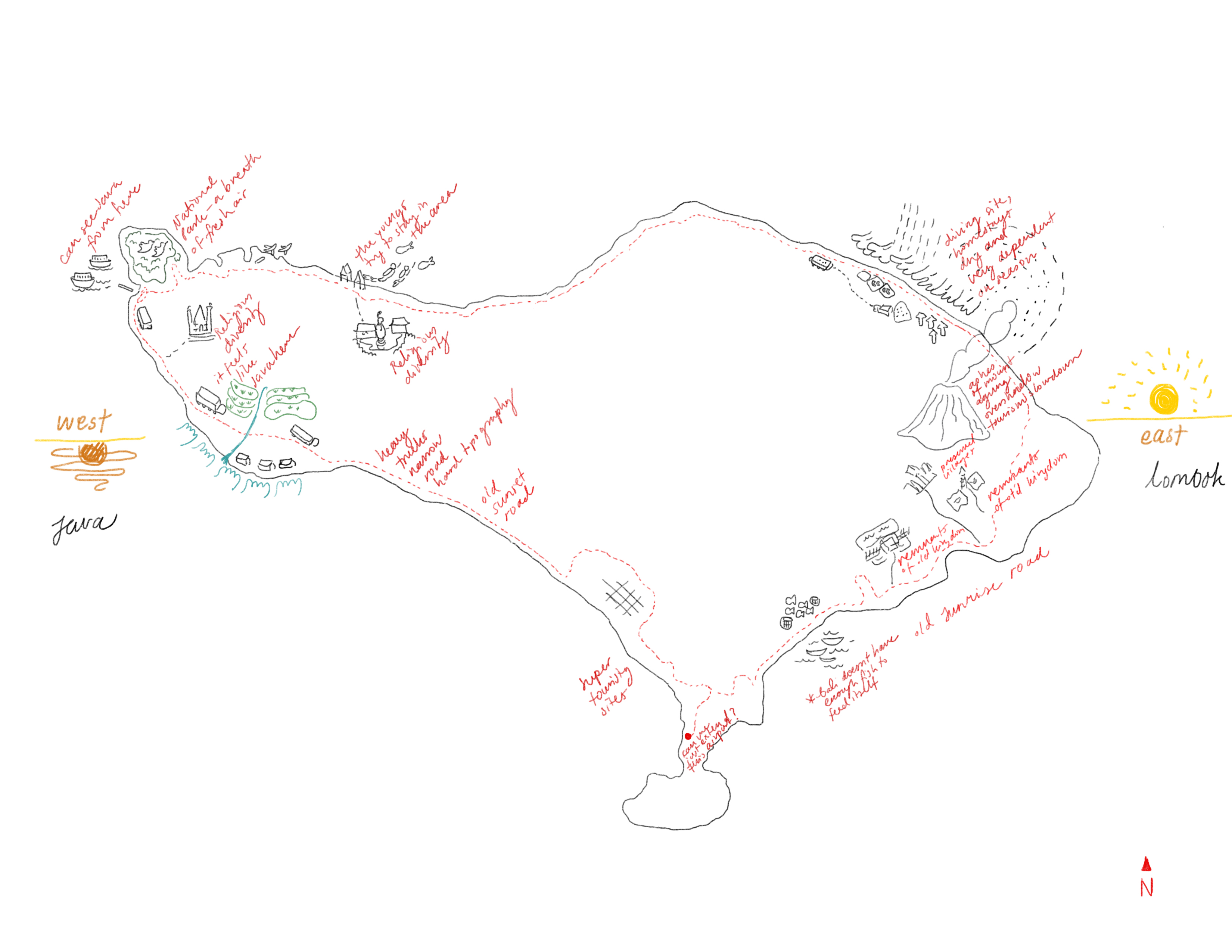

In January 2018, following a semester’s research on the Indonesian Countryside with Bali as the final site of investigation, I spend roughly two weeks doing fieldwork on site.

While the research itself focused on spatial planning and policy, I kept a visual diary to keep the sensual impressions and personal memories alive. After all, the urban and rural issues in Bali are not a mathematical problem, but a poetic one. The trip was divided into two, the first path was from north to south, and the second was around the perimeter of the island. Click here to read a complete annotated discoveries.

a visual diary

In January 2018, following a semester’s research on the Indonesian Countryside with Bali as the final site of investigation, I spend roughly two weeks doing fieldwork on site.

While the research itself focused on spatial planning and policy, I kept a visual diary to keep the sensual impressions and personal memories alive. After all, the urban and rural issues in Bali are not a mathematical problem, but a poetic one. The trip was divided into two, the first path was from north to south, and the second was around the perimeter of the island. Click here to read a complete annotated discoveries.

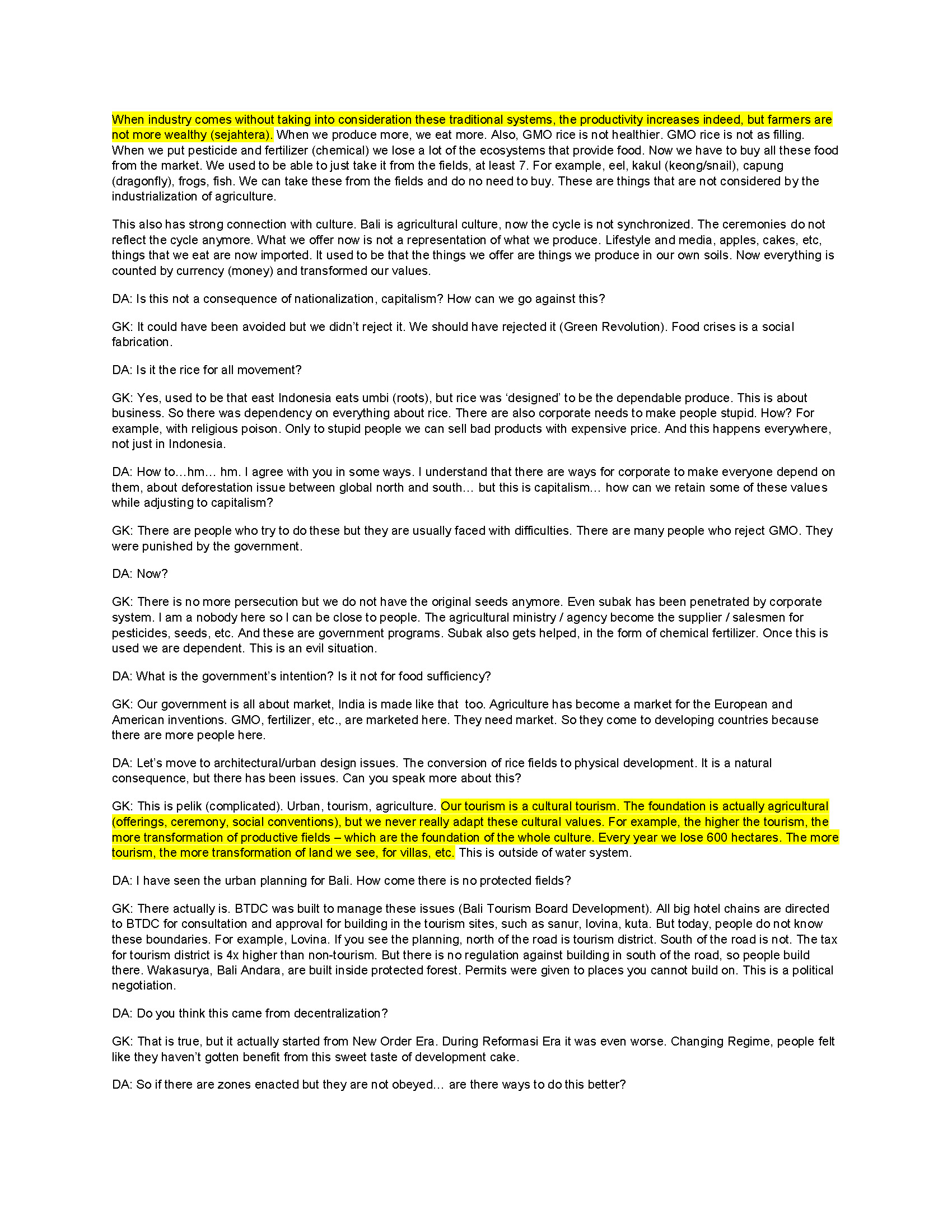

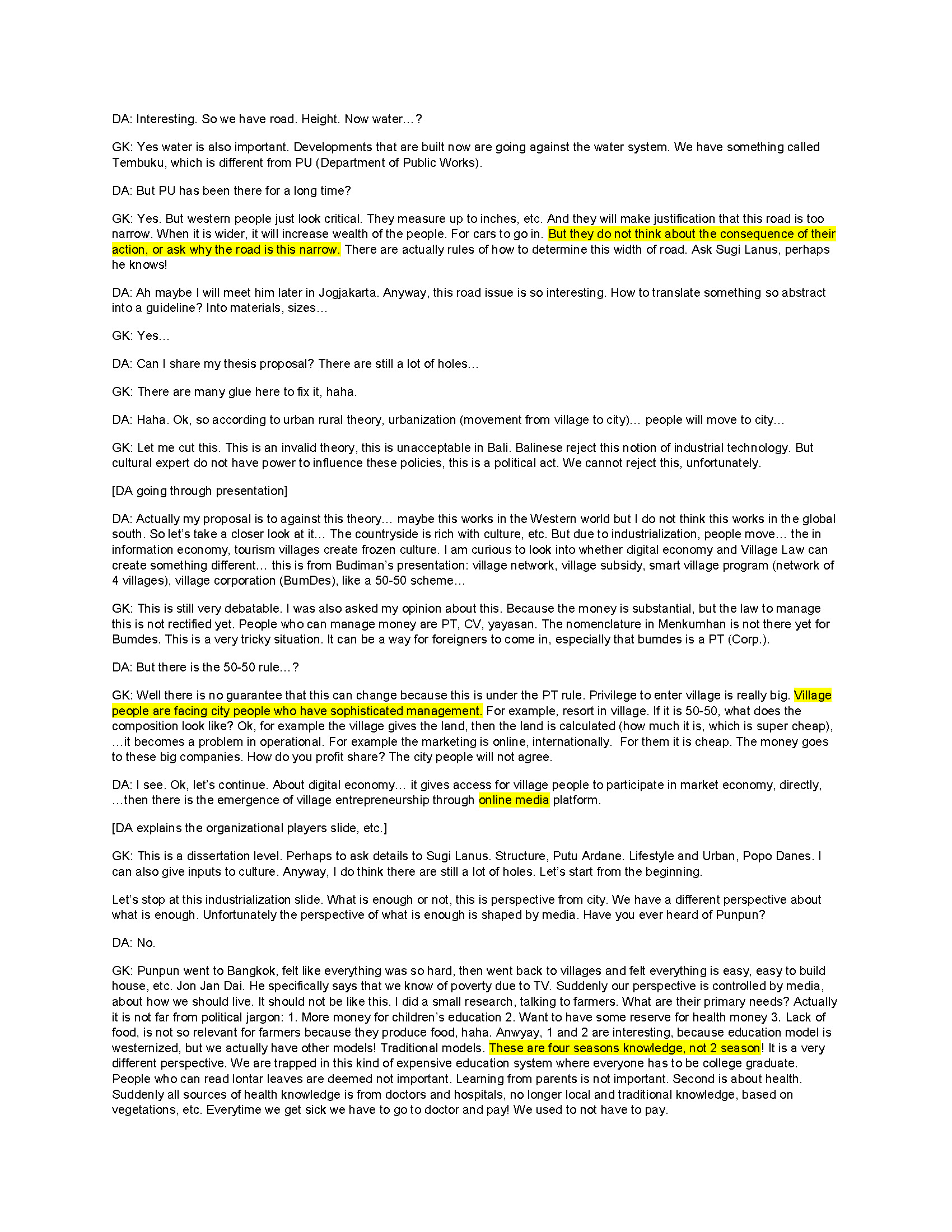

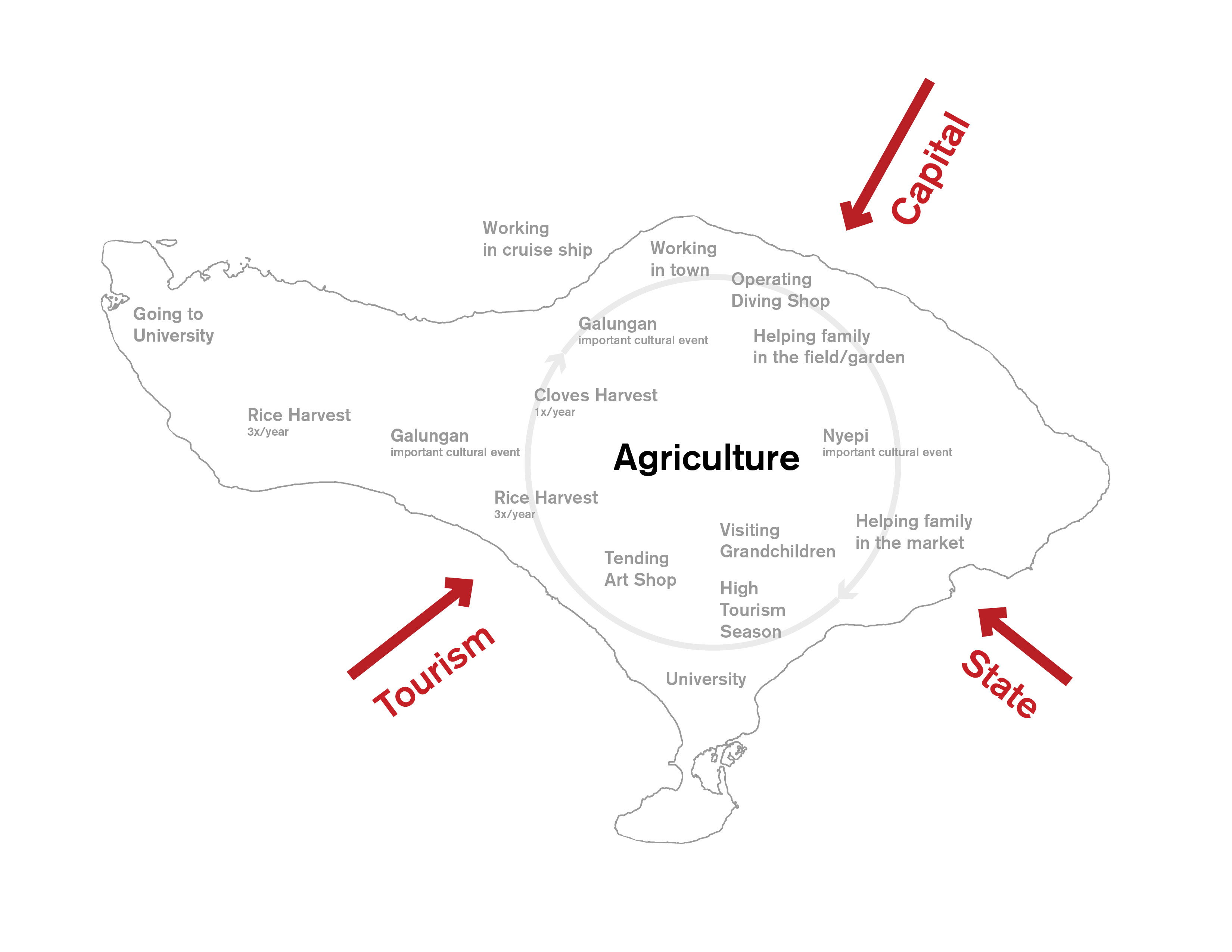

Understanding personal stories: interviews

Having a theoretical framework and data gathered, I wanted to understand the role of residents of rural areas from personal stories. I made a two-page fieldwork guideline as a framework during the trip. As we traveled across the island, we interviewed people from diverse age groups and professions, resulting in over forty pages of transcribed document, summarized in eight key takeaways, a starting point for the design proposal.

Having a theoretical framework and data gathered, I wanted to understand the role of residents of rural areas from personal stories. I made a two-page fieldwork guideline as a framework during the trip. As we traveled across the island, we interviewed people from diverse age groups and professions, resulting in over forty pages of transcribed document, summarized in eight key takeaways, a starting point for the design proposal.

Part II: Analysis

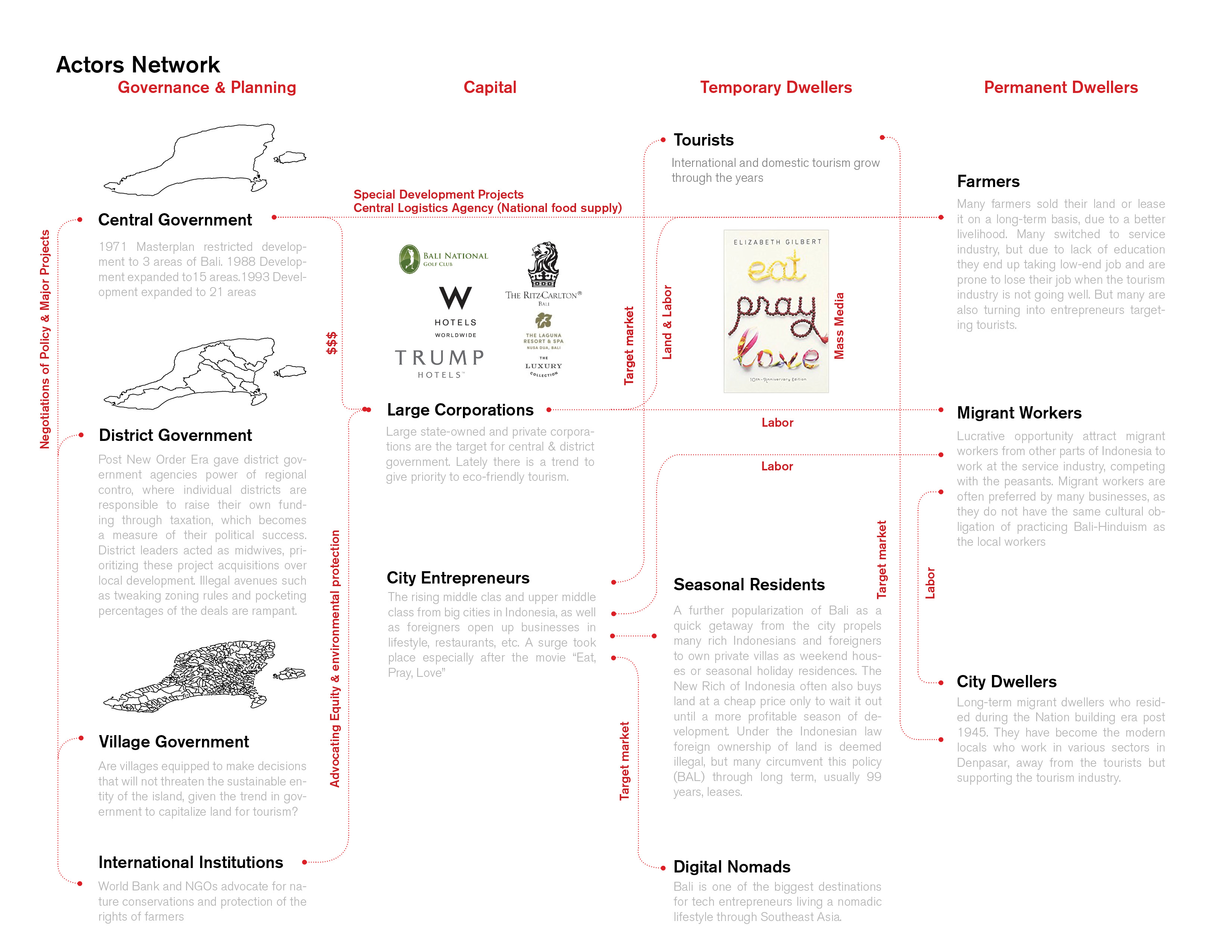

Stakeholder relationship analysis & problems

Part III: Proposal

The Slow Zone

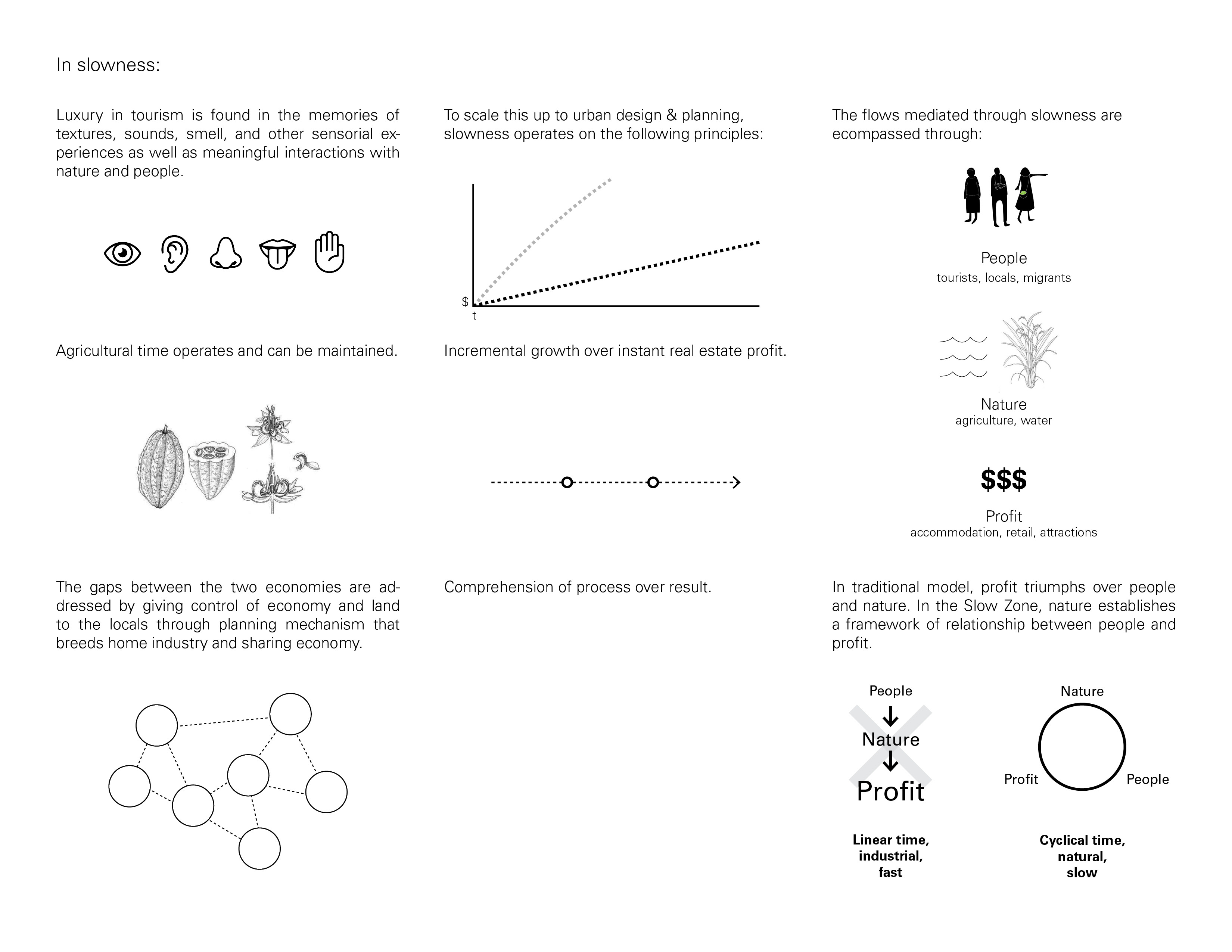

The Slow Zone is an alternative framework of thinking. Slowness means taking the time not just in daily pace, but development pace, to build village-based infrastructure that bridges the gaps between the two economies: skills gap, cultural gap, and environmental understanding gap. It means incremental growth over instant real estate profit. Meaningful interaction over monetary transaction. The tending of landscape as a source of economy.

The Slow Zone is an alternative framework of thinking. Slowness means taking the time not just in daily pace, but development pace, to build village-based infrastructure that bridges the gaps between the two economies: skills gap, cultural gap, and environmental understanding gap. It means incremental growth over instant real estate profit. Meaningful interaction over monetary transaction. The tending of landscape as a source of economy.

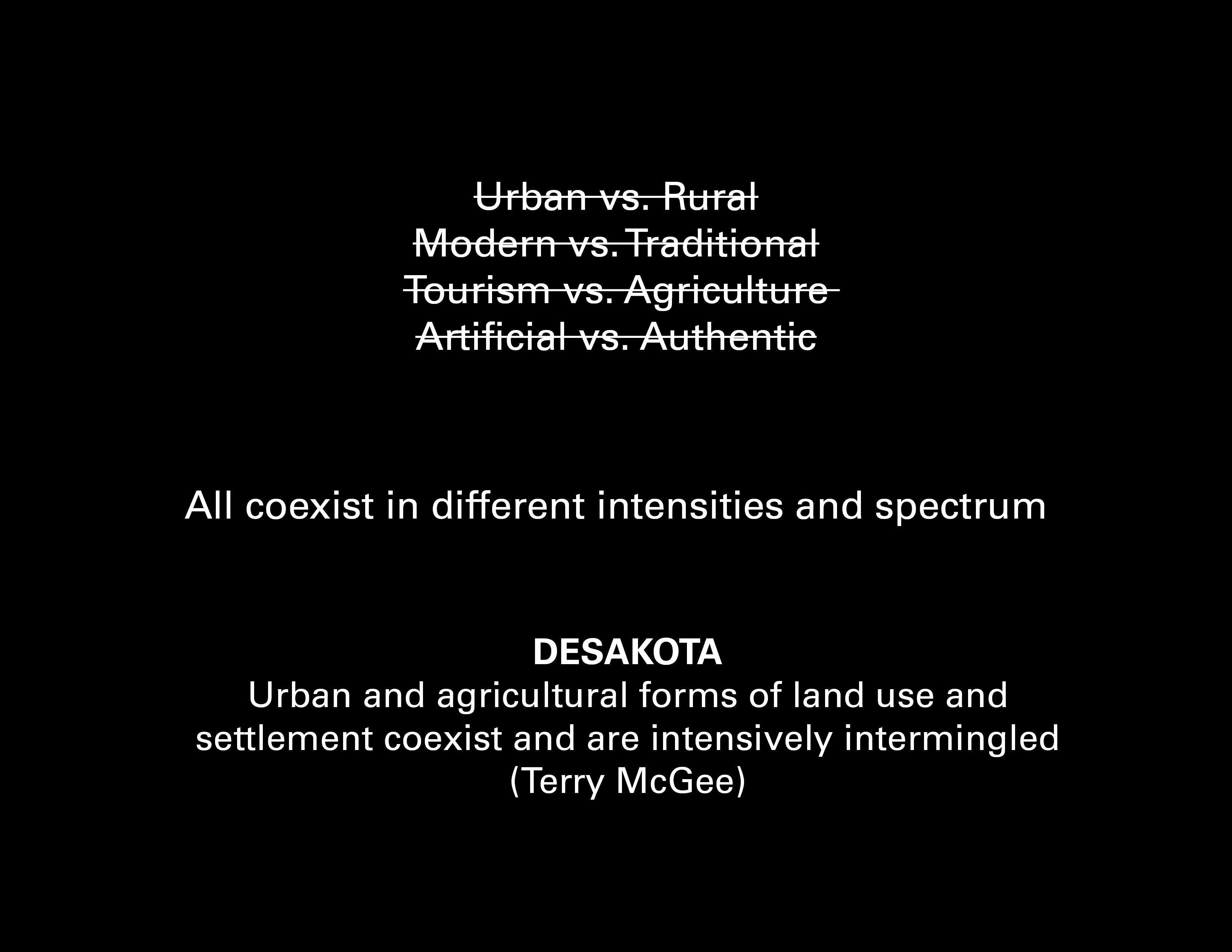

Theoretical framework

For this, we need to see that the progress seemingly embedded in the dualism used to describe Bali do not exist. Rural to Urban, Traditional to Modern, Agriculture to Tourism, Authentic to Artificial. All coexist in different intensities and spectrum. We need to see Bali as desakota, a term coined by Terry McGee, where urban and agricultural forms of land use and settlement coexist and are intensively intermingled.

For this, we need to see that the progress seemingly embedded in the dualism used to describe Bali do not exist. Rural to Urban, Traditional to Modern, Agriculture to Tourism, Authentic to Artificial. All coexist in different intensities and spectrum. We need to see Bali as desakota, a term coined by Terry McGee, where urban and agricultural forms of land use and settlement coexist and are intensively intermingled.

Methodology

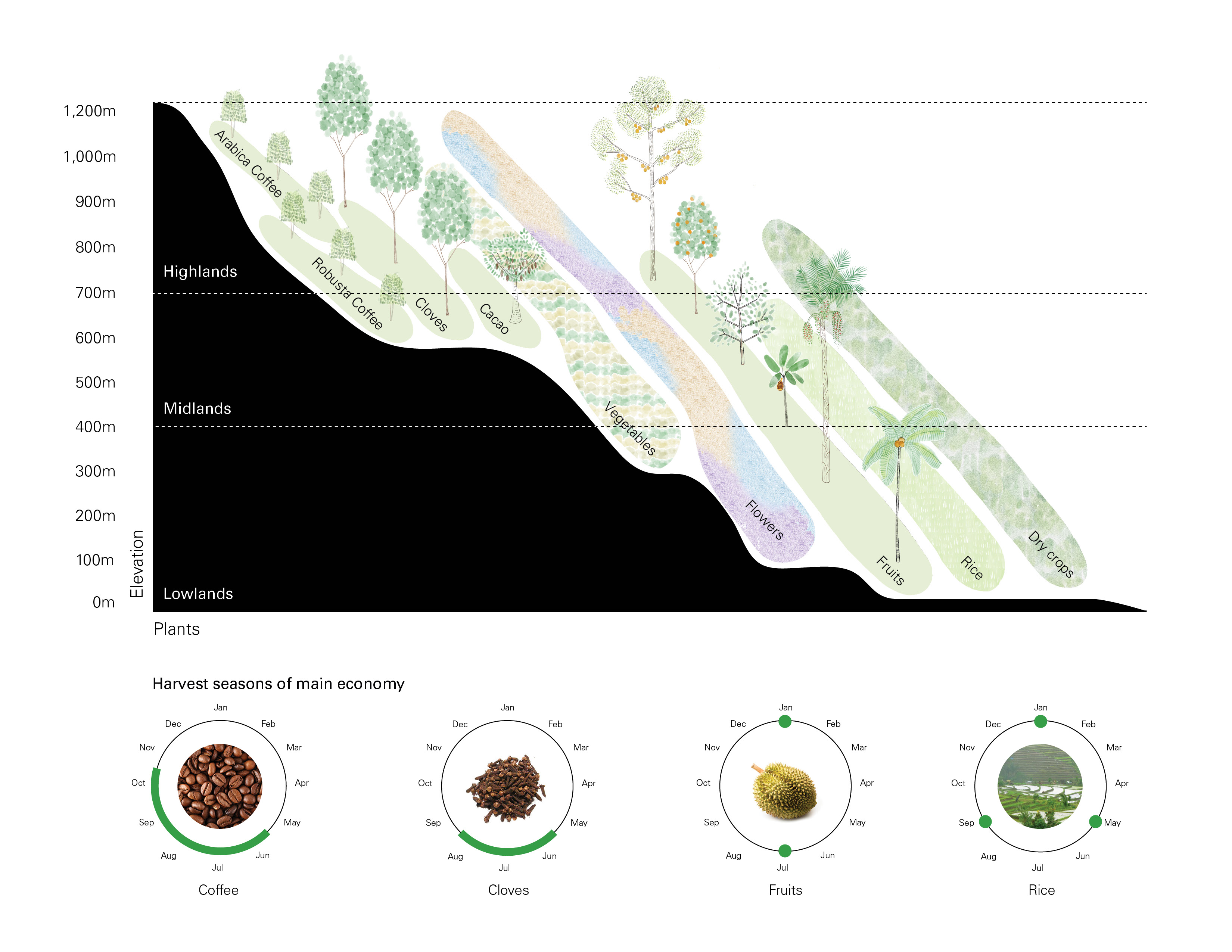

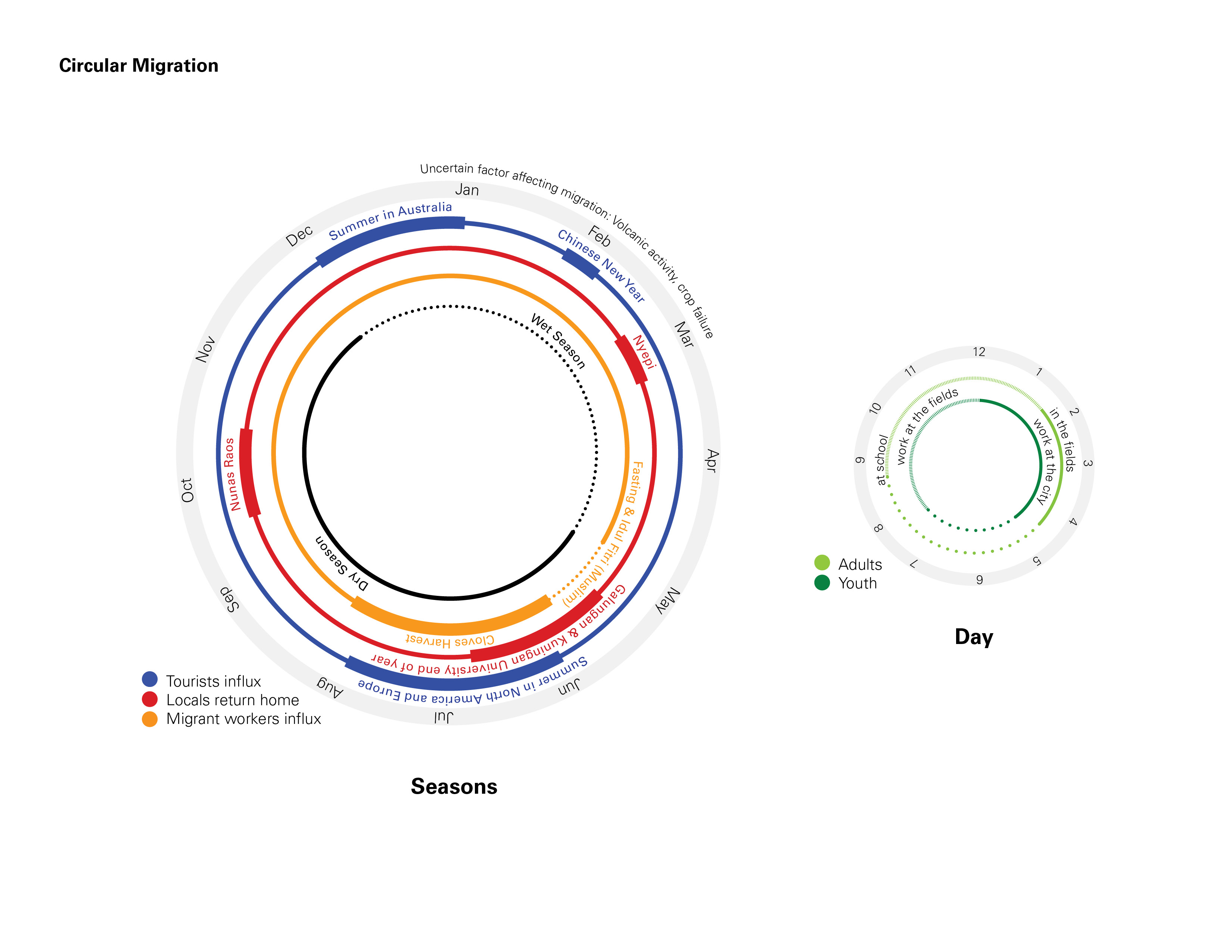

When nature becomes the baseline, we need to understand not only what can grow where, but also why. The history of agriculture in Bali is a political and man-made geography increasingly driven by global supply and demand, affecting the flows of people (tourists, migrant workers, and locals) as well as being affected by climate change.

When nature becomes the baseline, we need to understand not only what can grow where, but also why. The history of agriculture in Bali is a political and man-made geography increasingly driven by global supply and demand, affecting the flows of people (tourists, migrant workers, and locals) as well as being affected by climate change.

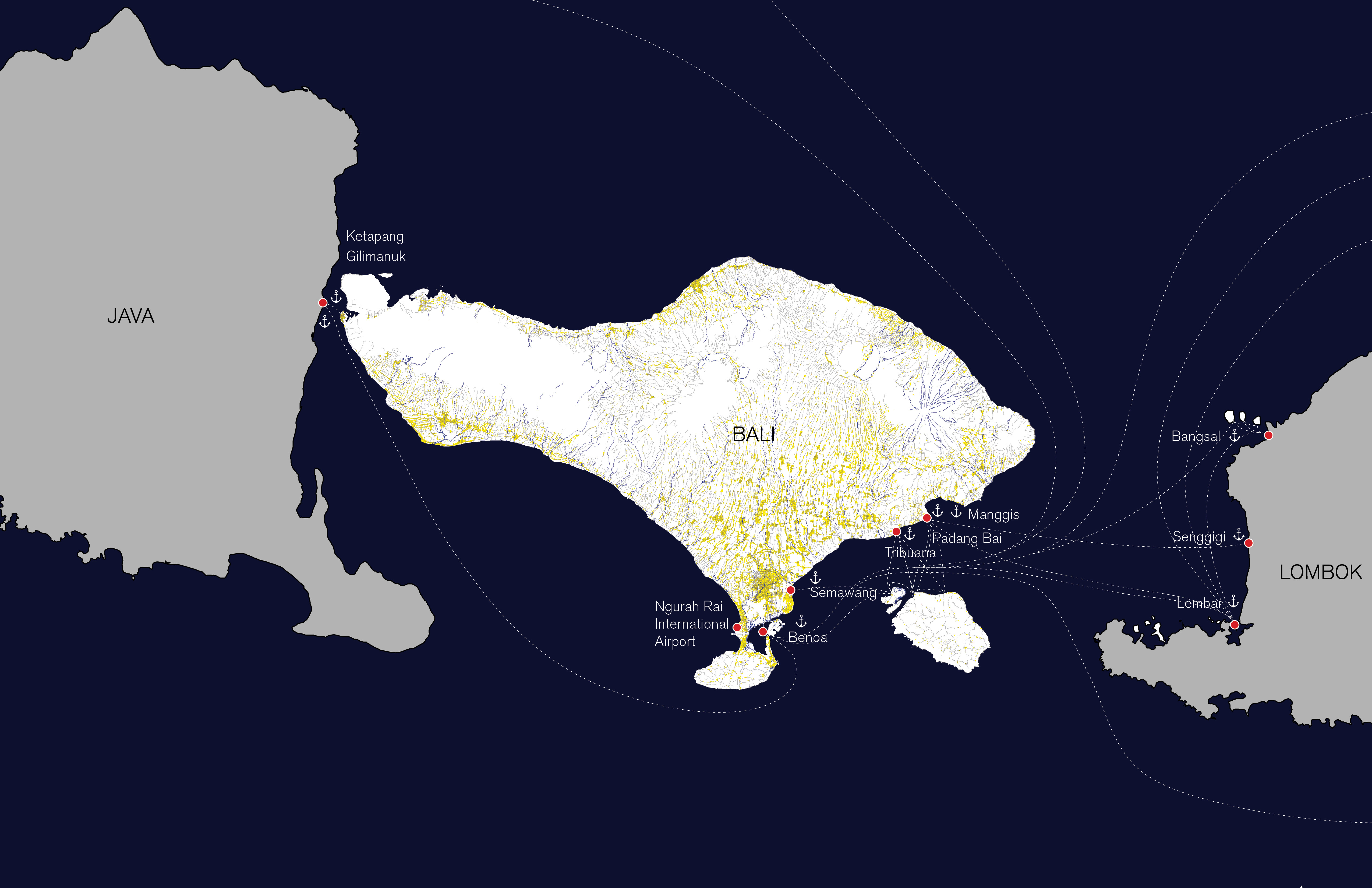

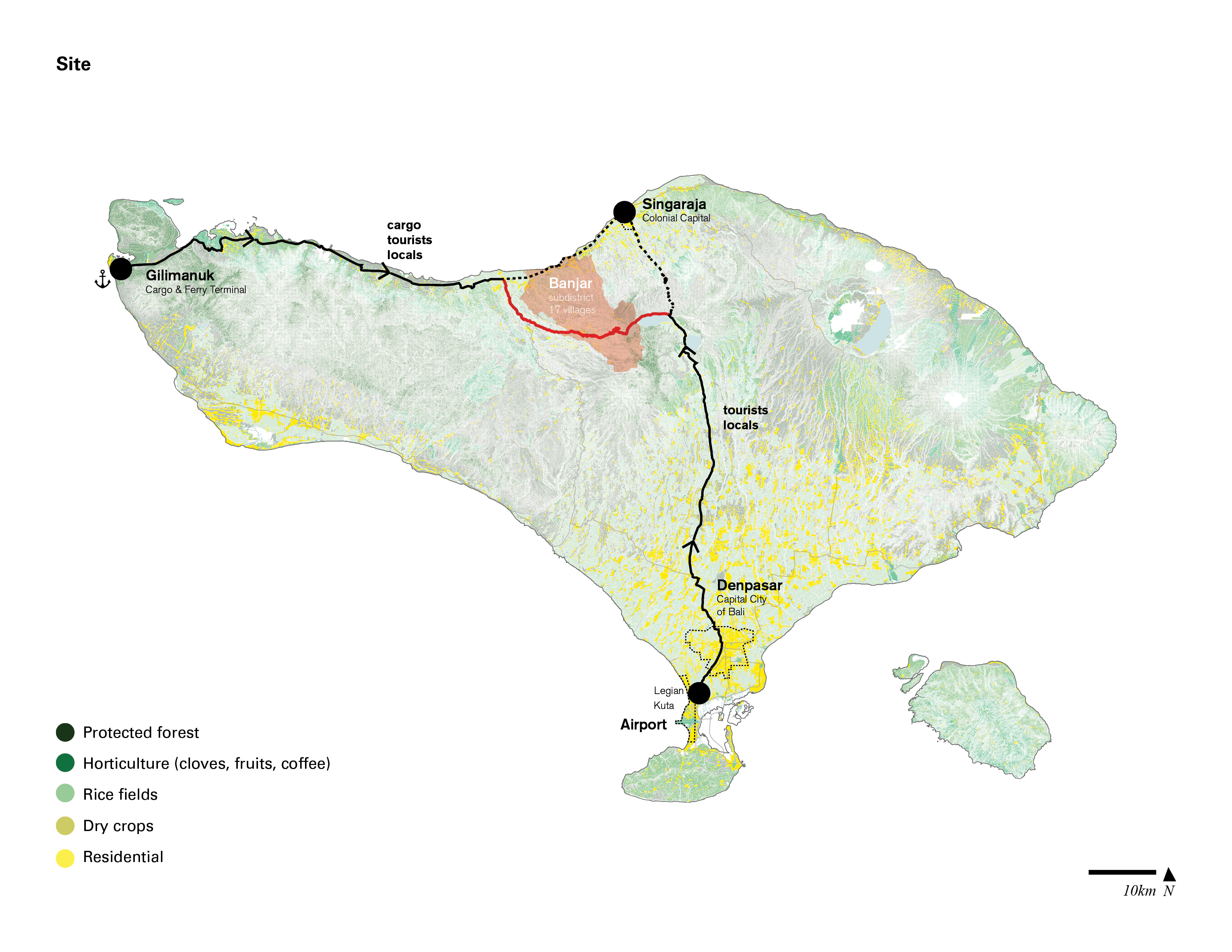

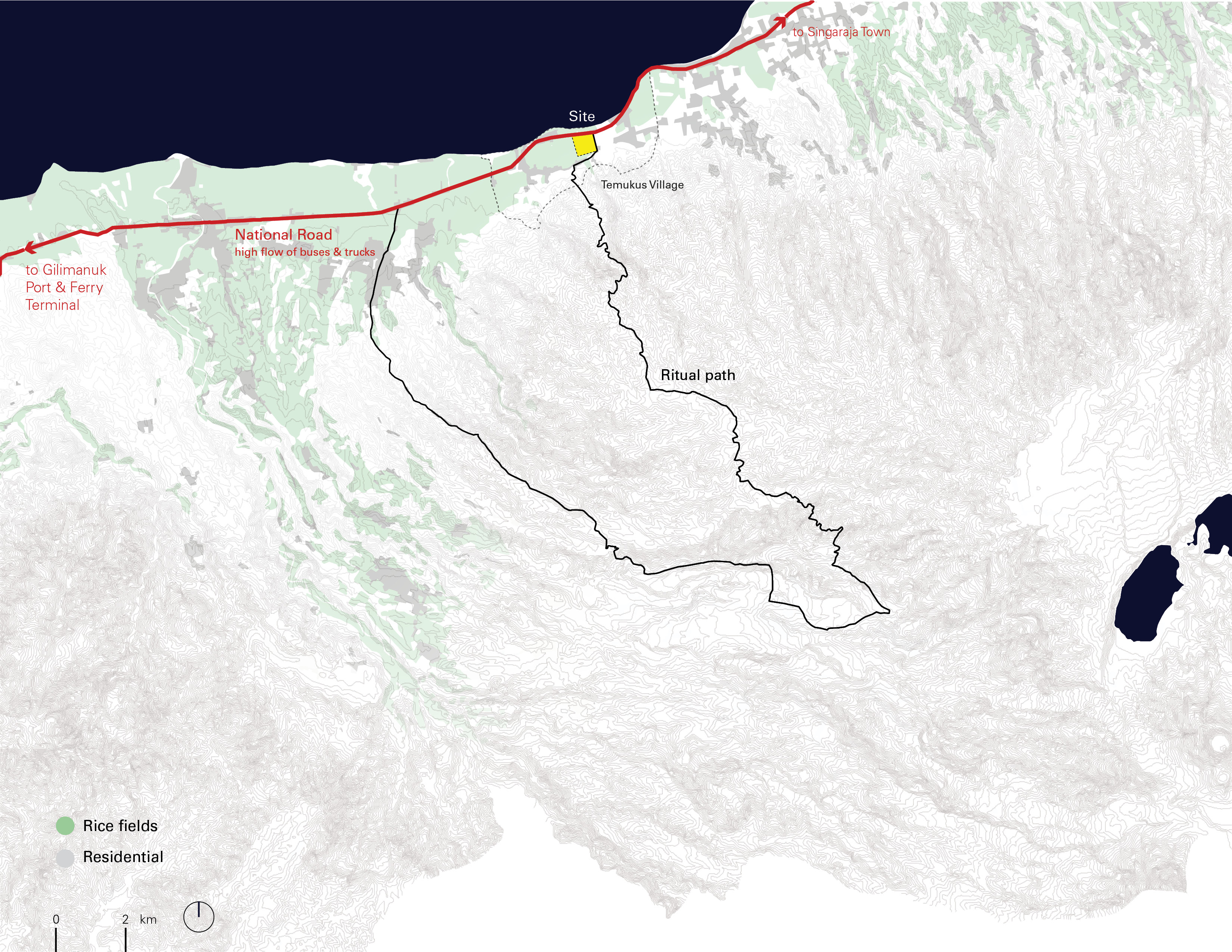

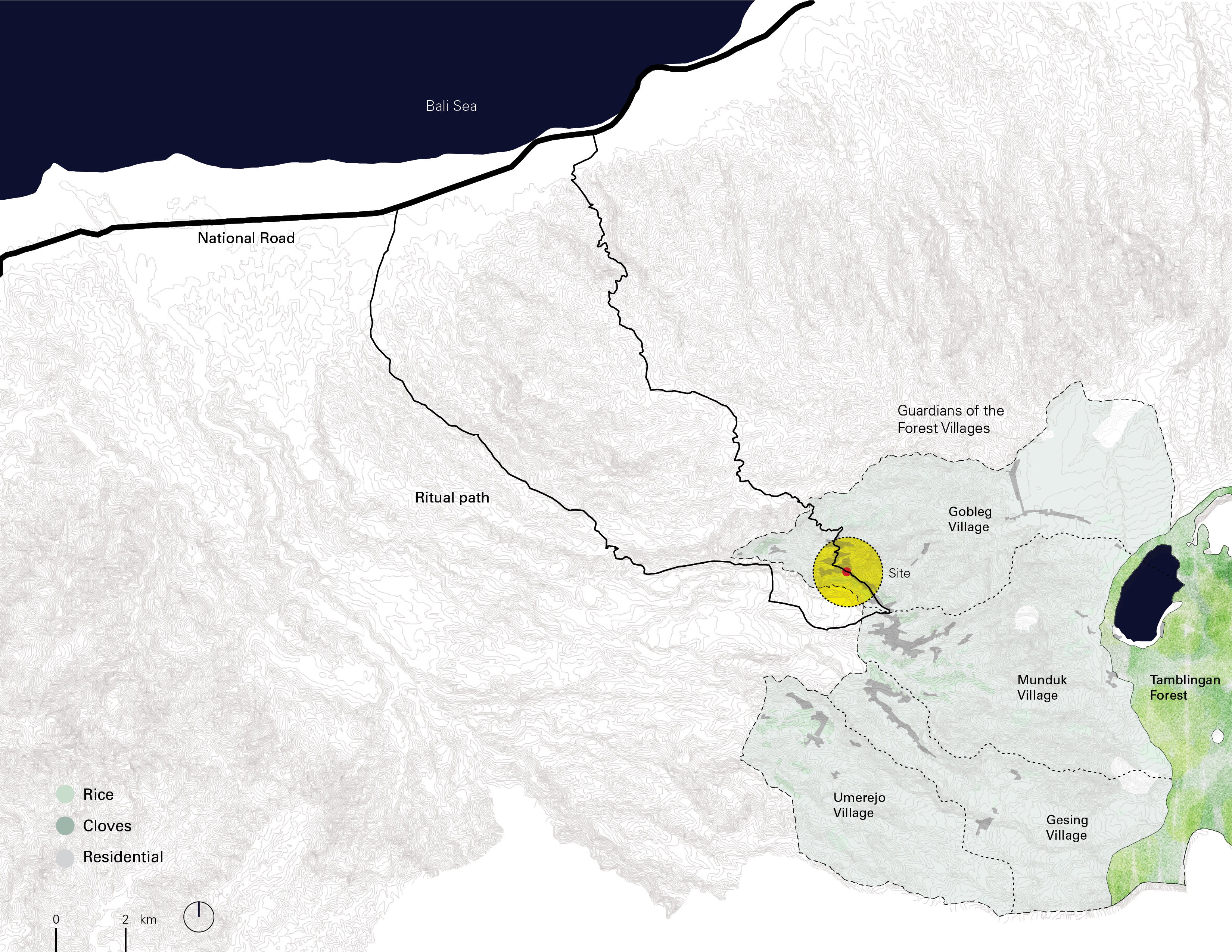

Site selection

The site is an area called Banjar Subdistrict with close proximity to the old capital city in North Bali.

The site is an area called Banjar Subdistrict with close proximity to the old capital city in North Bali.

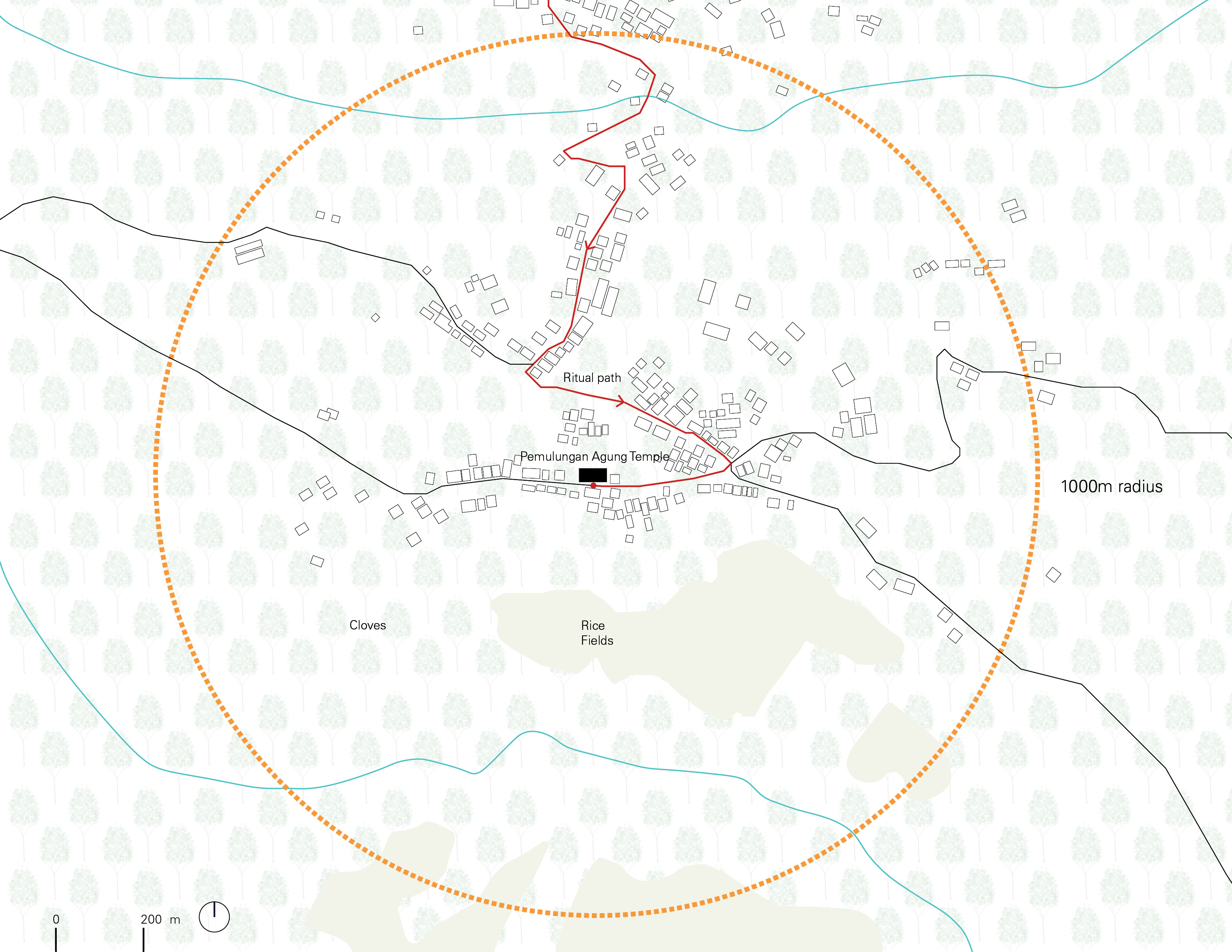

Site analysis: Networks beyond village boundaries

Villages operate on networks beyond administrative boundaries. Subak is a highly efficient ancient water irrigation cooperatives structure that is still being used until today.

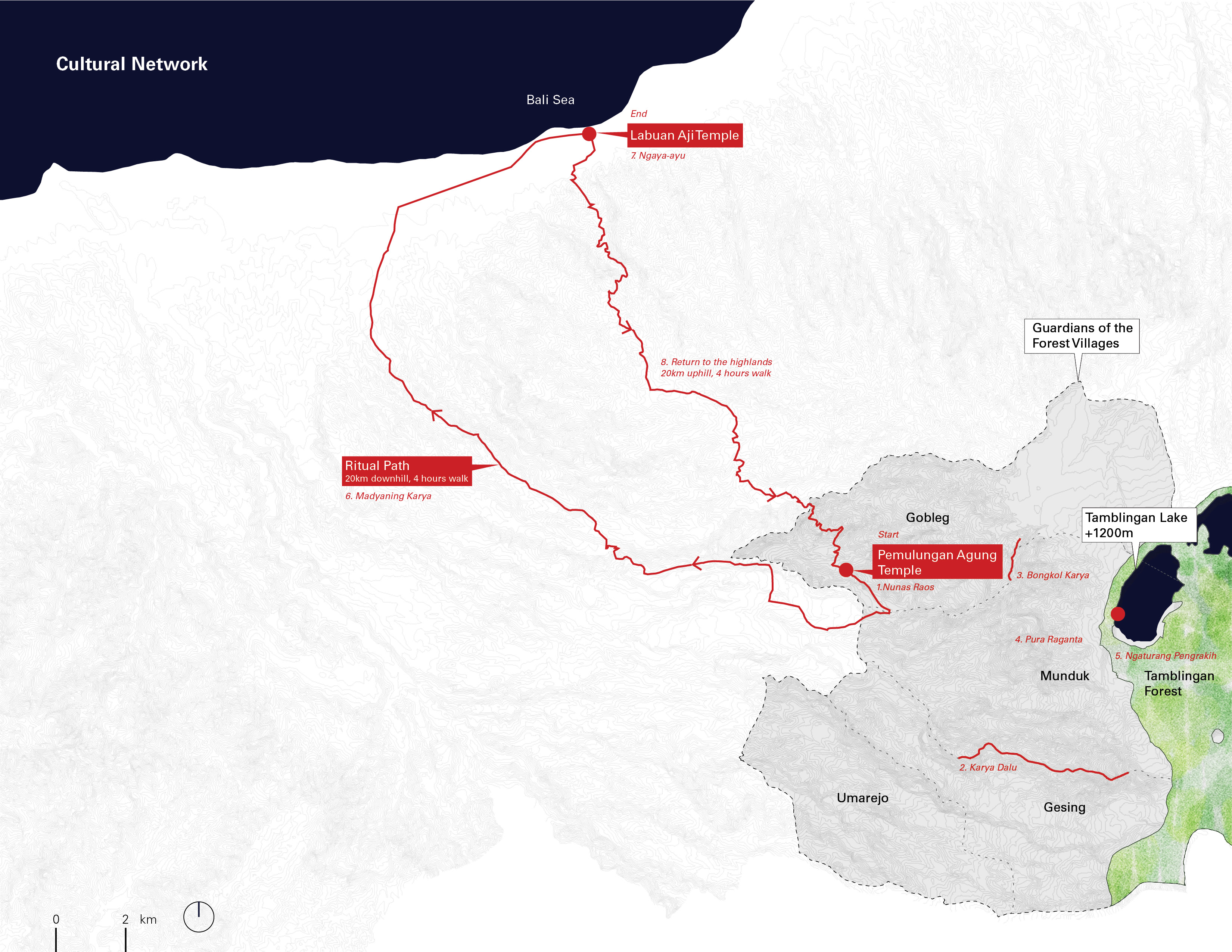

Cultural Network as Catalyst

Balinese celebrates many rituals that relates to the mountain and sea as two axes. The four villages in the hilltop are known as “the guardians of the forest.” The forest controls the water that flows to irrigate the lands below. Every two years for four months, residents in the four villages gather to sanctify the water through a series of ceremonies, culminating in a walk to the sea, and back up again, with over one thousand participants. During this time, villages along the path will participate.

Balinese celebrates many rituals that relates to the mountain and sea as two axes. The four villages in the hilltop are known as “the guardians of the forest.” The forest controls the water that flows to irrigate the lands below. Every two years for four months, residents in the four villages gather to sanctify the water through a series of ceremonies, culminating in a walk to the sea, and back up again, with over one thousand participants. During this time, villages along the path will participate.

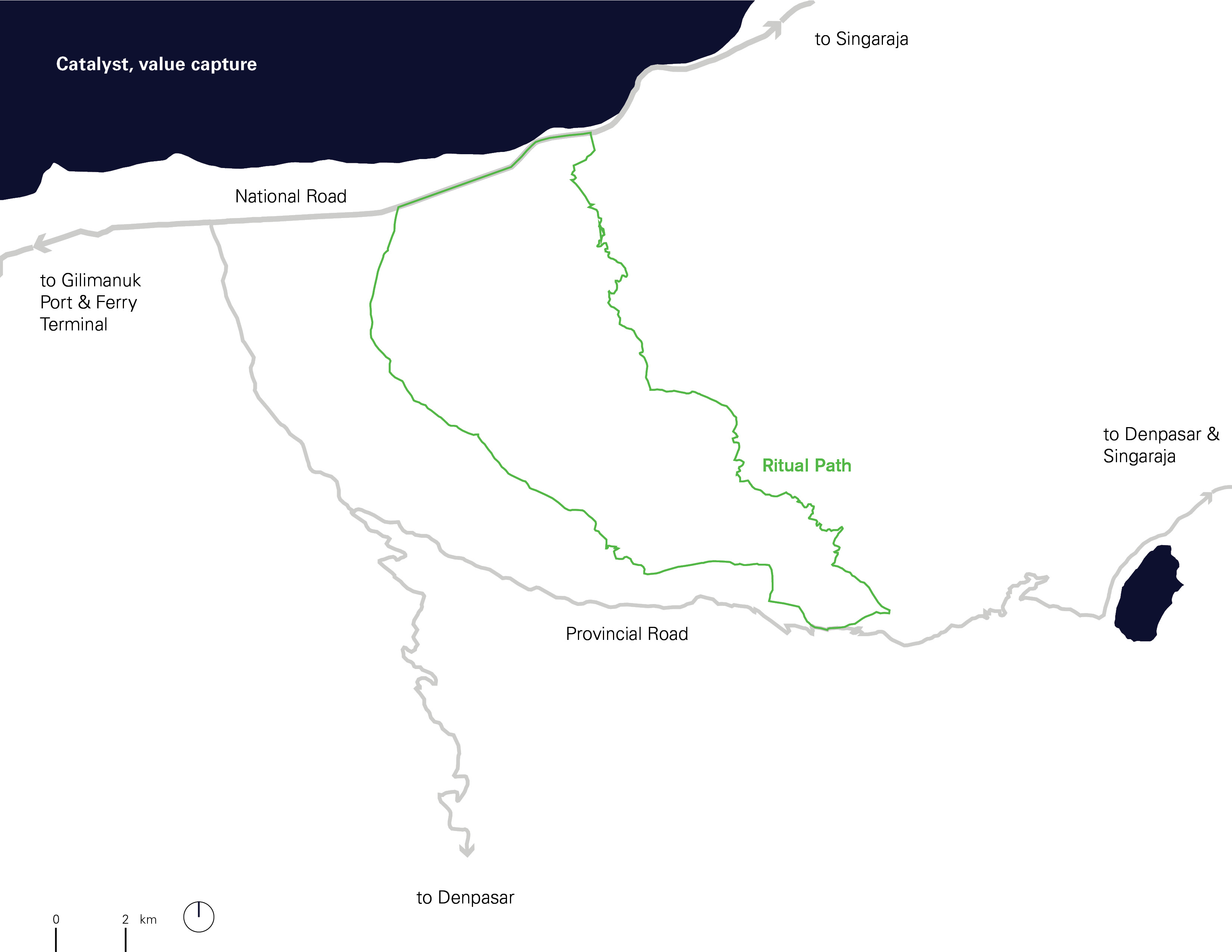

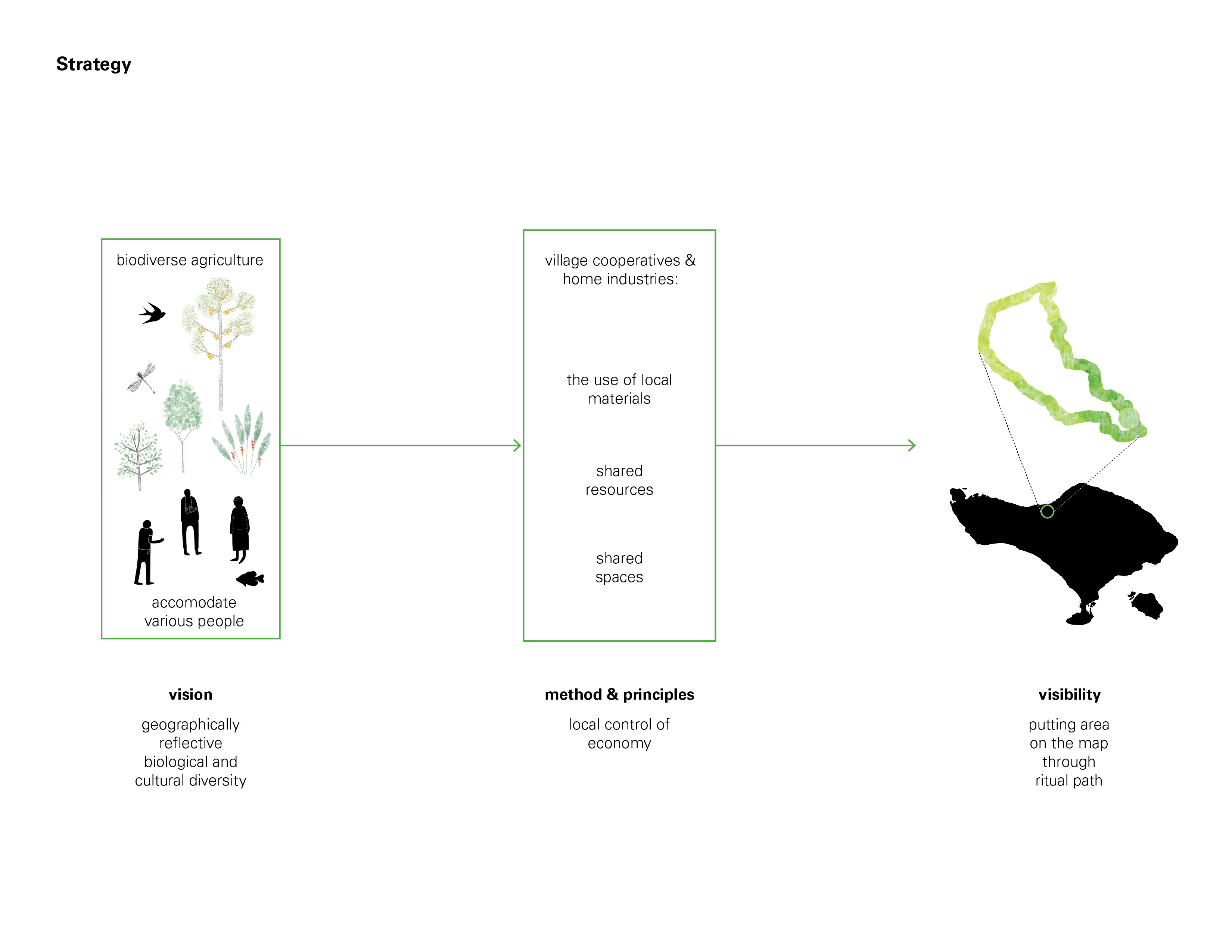

Slow Tourism

The project takes the ritual path as catalyst for development. Its vision is to bring back, and when possible, increase biological and cultural diversity through local control of economy, relying on shared resources, shared spaces, and local materials. The thesis demonstrates three models of development for three sites along the slow zone, in the lowlands, midlands, and highlands

The project takes the ritual path as catalyst for development. Its vision is to bring back, and when possible, increase biological and cultural diversity through local control of economy, relying on shared resources, shared spaces, and local materials. The thesis demonstrates three models of development for three sites along the slow zone, in the lowlands, midlands, and highlands

The Lowlands: Mixed-Use Development

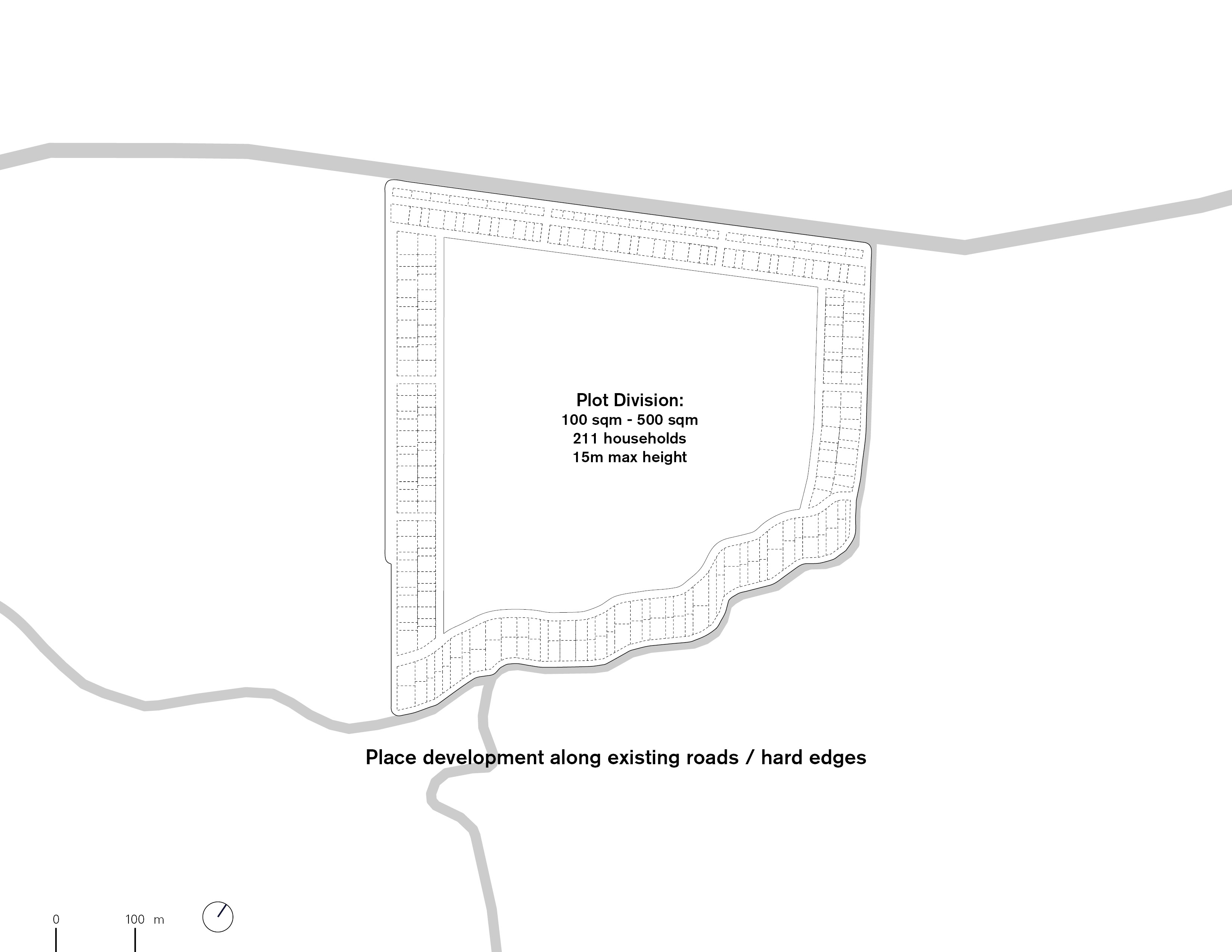

The areas with the most rapid conversion of rice fields is closest to the main roads. There is a saying, whenever a road is built, “Kavlingan” or land parceling, happens.

The water cooperatives (Subak) is among the most sophisticated method of organizing rice fields in ancient Bali that is still carried until today. The organization is a politically and culturally powerful entities, which gives permission and fines/dues for conversion of land use in villages. Building in conversion and development rules on top of fines can be a step further in control over local economy and land.

The pooling of land ownership acknowledges that no one farmer is as strong as outside capital, and that shared financial resources and management is not only one way to retain local control but also play on the strength of villages as being formed by strong sense of community. At the same time, developing larger quantity of land instead of individual parcels give more room to control environmental, social, and cultural impacts.

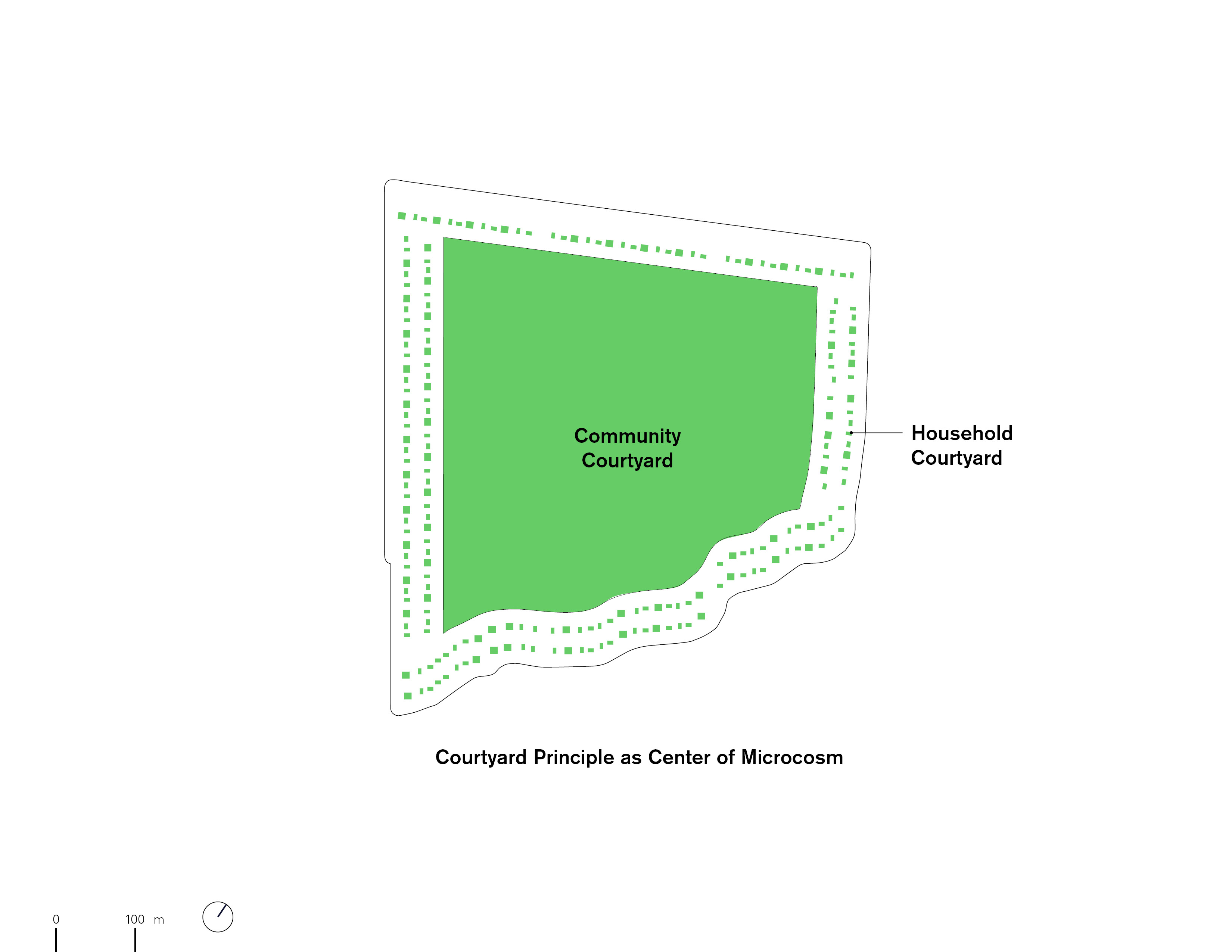

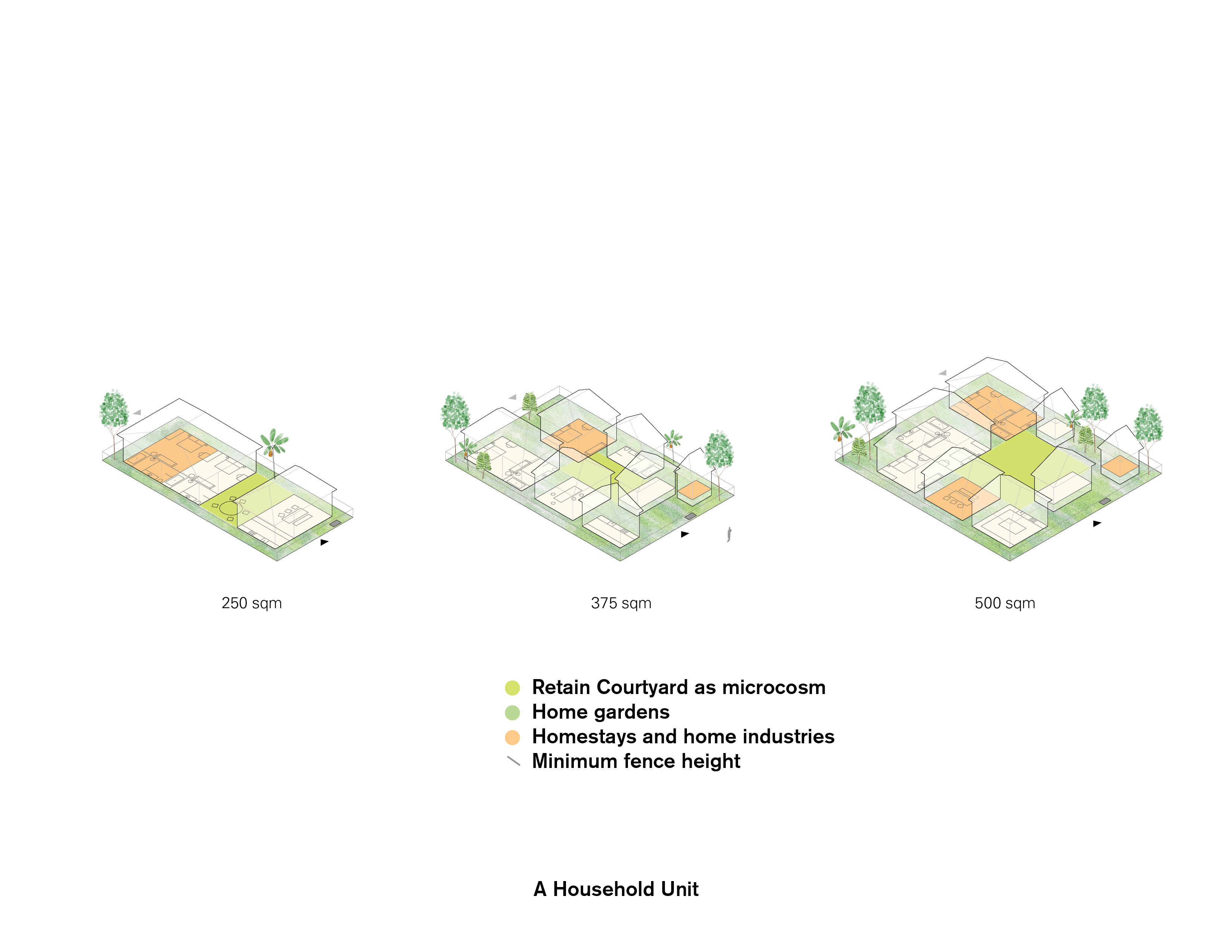

Village Mixed-Use Development proposes a co-op model where commercial development such as housing and businesses can take place while still retaining agricultural aspects, balancing two economies and ensuring profitability for the villagers.

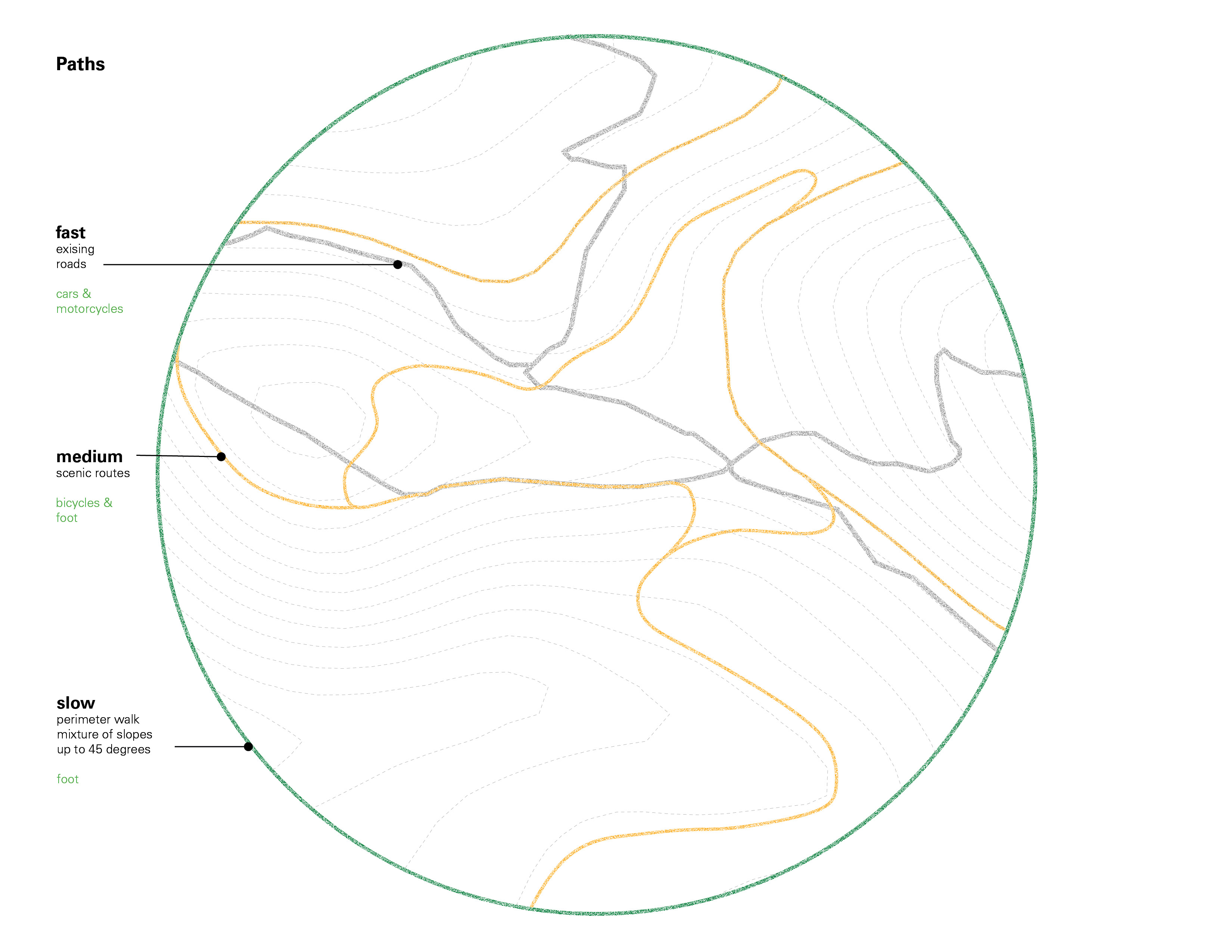

Agricultural fields are best left operating undisturbed due to potential for pollution and shared nutrients in continuous soil. The zoning proposes the preservation of maximum agricultural fields utilizing existing roads, with maximum built up zone of 30%, the proportion that balances commercial and agricultural development.

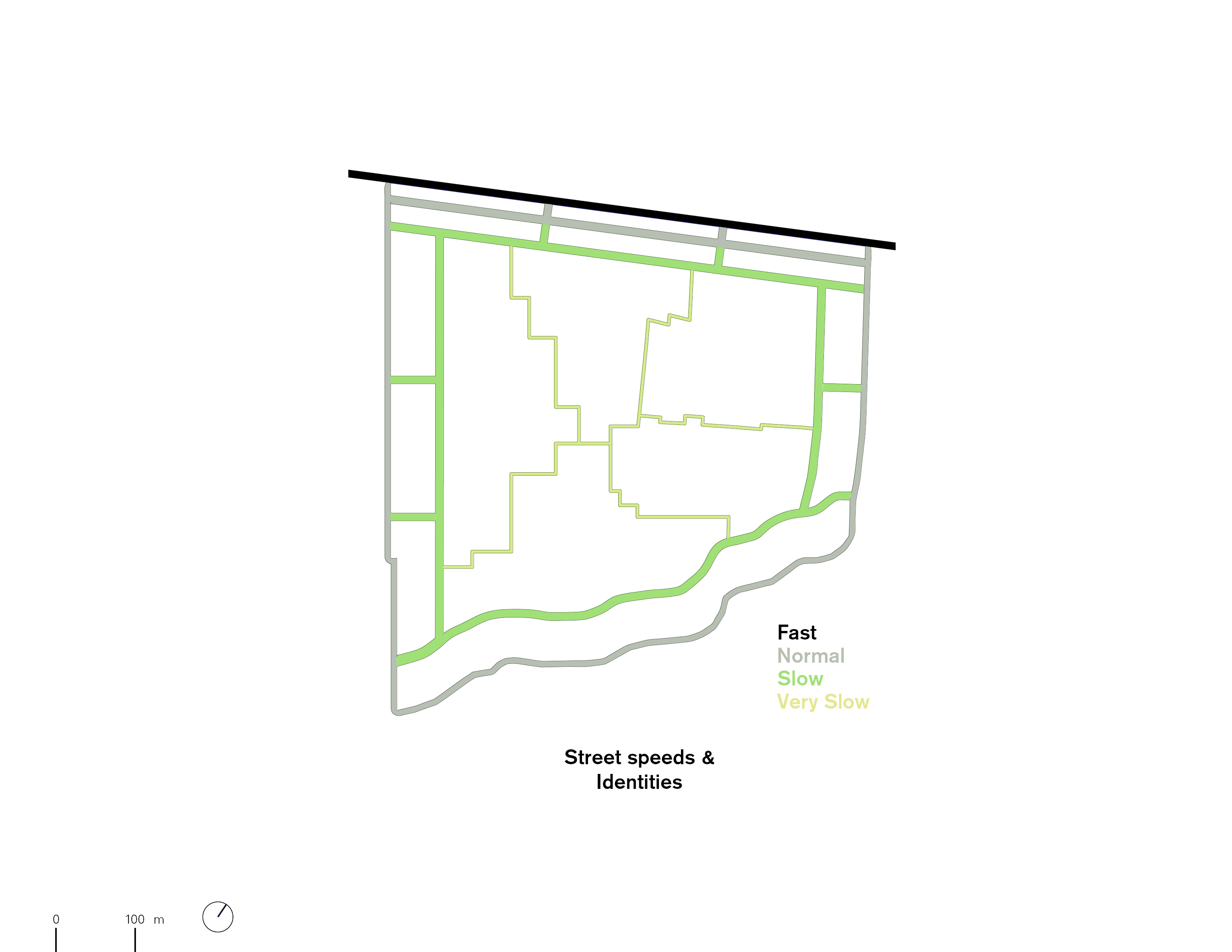

The streets are zoned into normal, slow, and slowest. Different frontages give way to unique and flexible codes of development, for example, commercial facing, cultural facing, and agricultural facing streets. The slow zone also penetrates the household scale by requiring percentage of greeneries to not only be green but also functions as home gardens. Within this mixed use zone many local economies thrive, slow restaurant, slow gardening, et cetera.

The areas with the most rapid conversion of rice fields is closest to the main roads. There is a saying, whenever a road is built, “Kavlingan” or land parceling, happens.

The water cooperatives (Subak) is among the most sophisticated method of organizing rice fields in ancient Bali that is still carried until today. The organization is a politically and culturally powerful entities, which gives permission and fines/dues for conversion of land use in villages. Building in conversion and development rules on top of fines can be a step further in control over local economy and land.

The pooling of land ownership acknowledges that no one farmer is as strong as outside capital, and that shared financial resources and management is not only one way to retain local control but also play on the strength of villages as being formed by strong sense of community. At the same time, developing larger quantity of land instead of individual parcels give more room to control environmental, social, and cultural impacts.

Village Mixed-Use Development proposes a co-op model where commercial development such as housing and businesses can take place while still retaining agricultural aspects, balancing two economies and ensuring profitability for the villagers.

Agricultural fields are best left operating undisturbed due to potential for pollution and shared nutrients in continuous soil. The zoning proposes the preservation of maximum agricultural fields utilizing existing roads, with maximum built up zone of 30%, the proportion that balances commercial and agricultural development.

The streets are zoned into normal, slow, and slowest. Different frontages give way to unique and flexible codes of development, for example, commercial facing, cultural facing, and agricultural facing streets. The slow zone also penetrates the household scale by requiring percentage of greeneries to not only be green but also functions as home gardens. Within this mixed use zone many local economies thrive, slow restaurant, slow gardening, et cetera.

The Midlands: Ancient Bali Intervillage Center & Transport Network

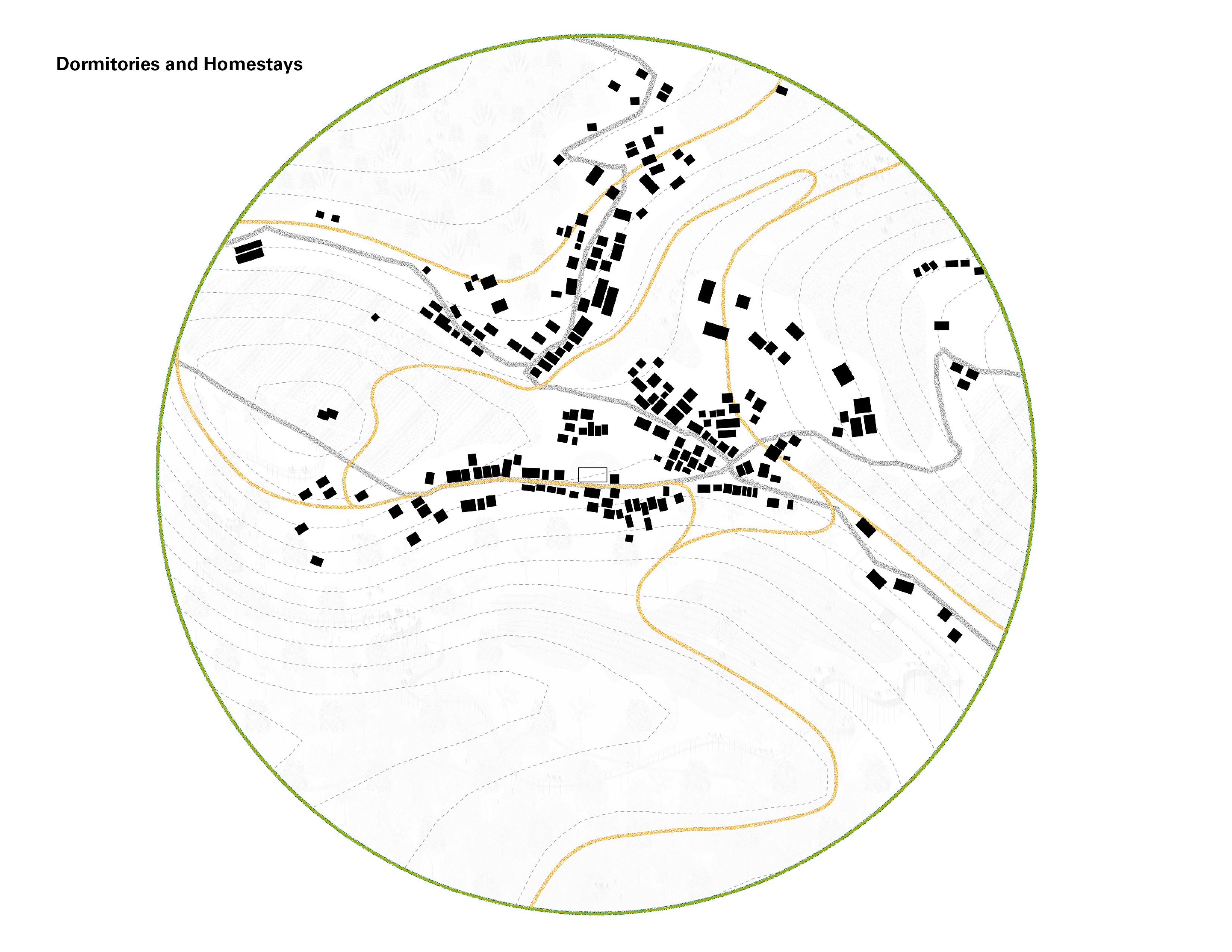

The five Ancient Bali Villages is known for their traditional way of life relying on natural resources, as reflected in the abundance of home industries, cultural practices, and the use of mudbrick for vernacular houses. Bamboo is used for making household products, whereas palm fruit is used for making palm sugar and drink. In recent years, the popularity of cloves as cash crops is slowly changing the landscape.

The midlands also produces fruits that supply the demands of tourism in the south, as well as domestic and international market. However, lack of access to markets often result in decaying oversupply of products. The five ancient villages are sparsely populated and located in a large. Past approaches to develop this area have focused on individual villages potential and unable to gain momentum. The design project proposes an intervillage market and transportation hub as a centralized access for the promotion of home industries.

The market intersects the ritual road and redevelops the current market. The building material displays artisanship and use of local materials. The program includes: Market for retail and wholesale trade; Information center & travel agencies; Training center for development of home industries; Food processing and packaging facilities.

The public space accommodates the flow of cultural procession. Bus terminal in the market facilitate the movement of goods, locals, and tourists among remote villages, such as: The bamboo forest, where tourists can learn and purchase directly from the makers; The durian festival and fruit plantations, where oversupply of fruits can be taken to the food processing facility; The palm fruit plantations, where visitors can see the process of palm sugar and drink making.

The philosophy of using natural materials are extended in the homestays as an effort to preserve architectural technique.

The five Ancient Bali Villages is known for their traditional way of life relying on natural resources, as reflected in the abundance of home industries, cultural practices, and the use of mudbrick for vernacular houses. Bamboo is used for making household products, whereas palm fruit is used for making palm sugar and drink. In recent years, the popularity of cloves as cash crops is slowly changing the landscape.

The midlands also produces fruits that supply the demands of tourism in the south, as well as domestic and international market. However, lack of access to markets often result in decaying oversupply of products. The five ancient villages are sparsely populated and located in a large. Past approaches to develop this area have focused on individual villages potential and unable to gain momentum. The design project proposes an intervillage market and transportation hub as a centralized access for the promotion of home industries.

The market intersects the ritual road and redevelops the current market. The building material displays artisanship and use of local materials. The program includes: Market for retail and wholesale trade; Information center & travel agencies; Training center for development of home industries; Food processing and packaging facilities.

The public space accommodates the flow of cultural procession. Bus terminal in the market facilitate the movement of goods, locals, and tourists among remote villages, such as: The bamboo forest, where tourists can learn and purchase directly from the makers; The durian festival and fruit plantations, where oversupply of fruits can be taken to the food processing facility; The palm fruit plantations, where visitors can see the process of palm sugar and drink making.

The philosophy of using natural materials are extended in the homestays as an effort to preserve architectural technique.

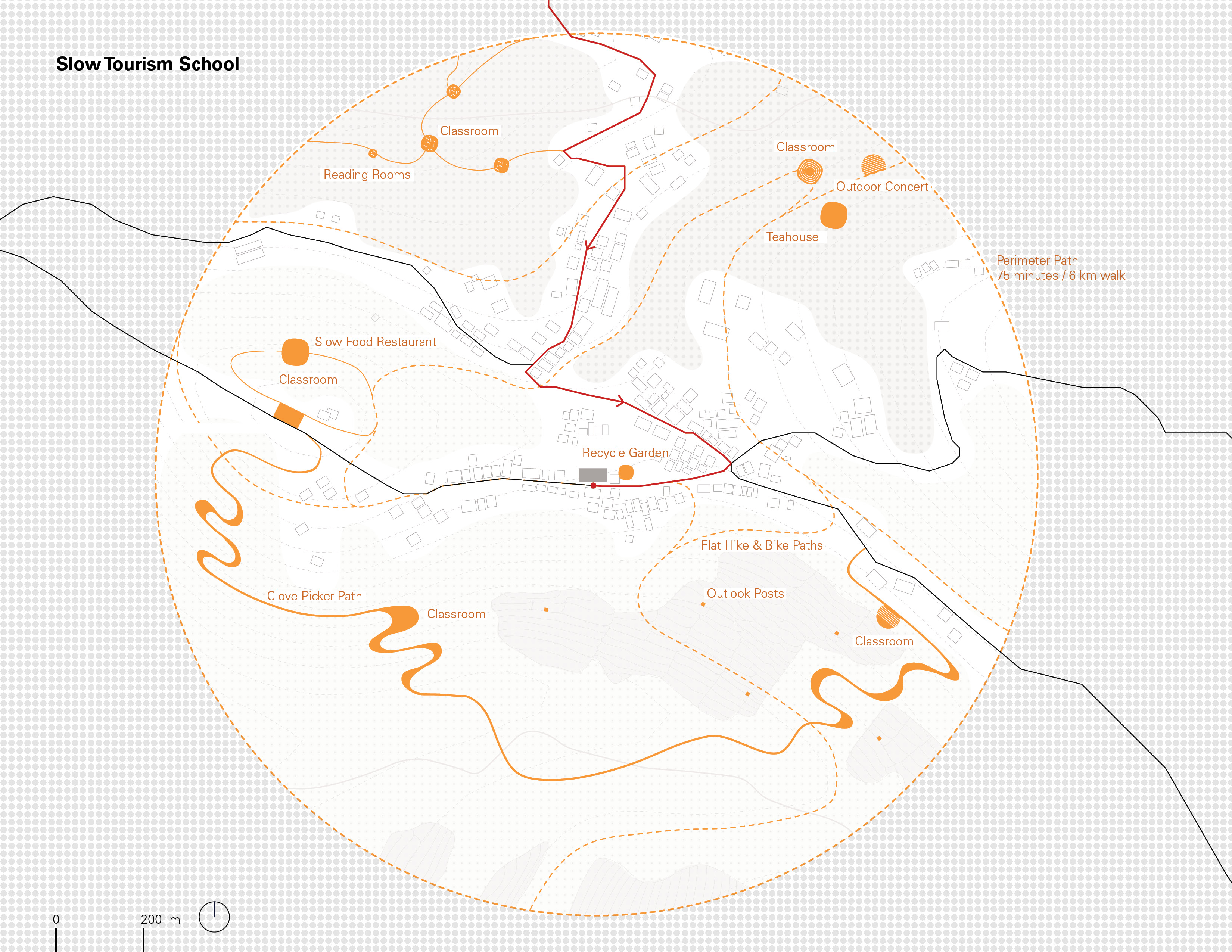

The Highlands: Sanctuary & Slow Tourism School

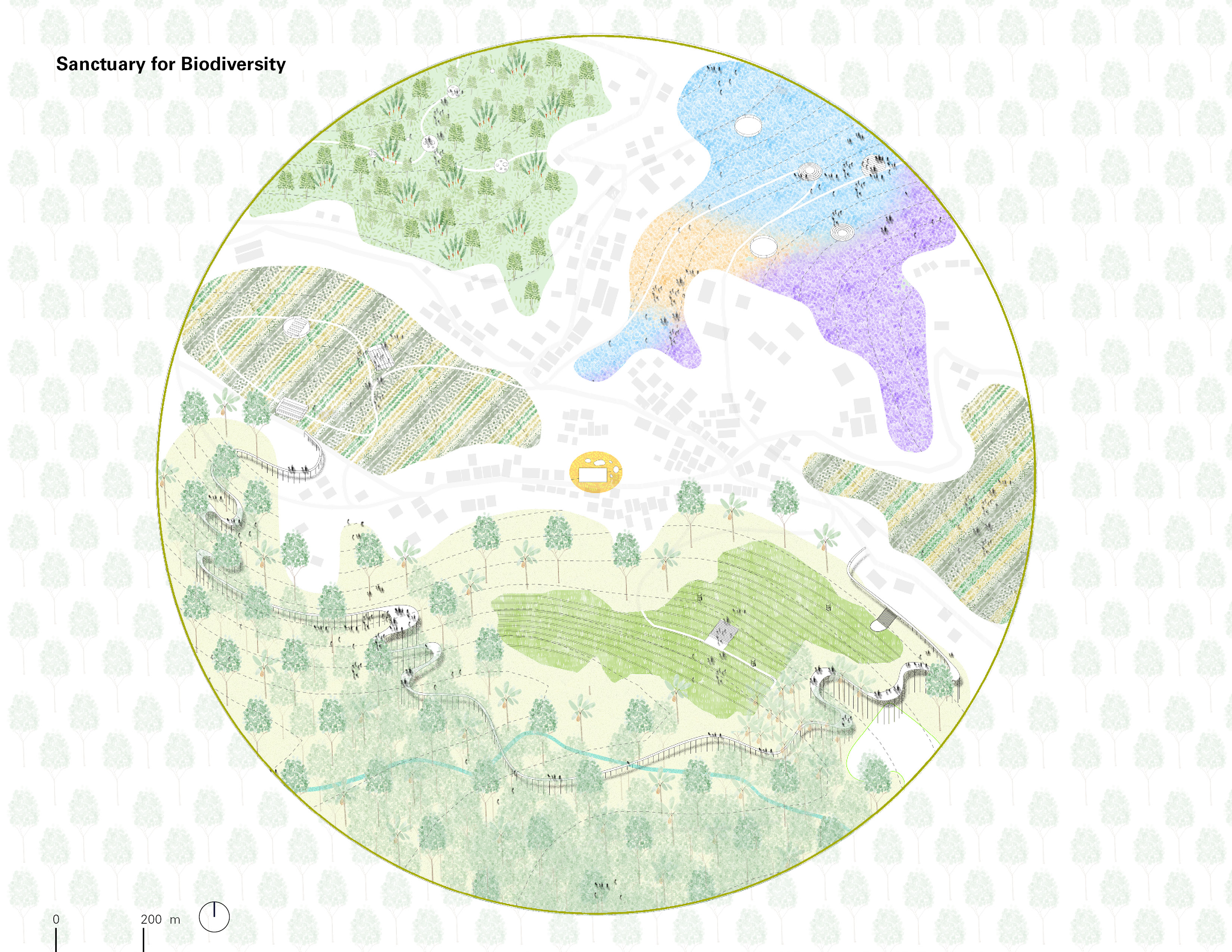

The highlands of Bali is the most fertile for all kinds of crops, making it one of places with the most biodiversity in North Bali.

In the 1980s, increased price of cloves to be used for tobacco industry create high value of cloves. Along with the failure of coffee in lower highlands, many farmers converted their rice fields, cocoa, coffee plantations, and spices such as vanilla into cloves and orange groves.

While the villages of highlands (the guardians of the forest) are financially prosperous and the economy and landscapes of cloves and coffee have brought a new kind of beauty and traditions, many are lamenting the change in attitude among villagers as proliferation of private hotels increase privacy among residents. At the same time, ecological biodiversity is threatened. For example, Cloves fruits and coffee beans are not consumable by birds, breaking the ecology chain and reducing biodiversity in the area.

Development has resulted in the intensive use of plastic products that pollute the environment, and subsequently their identity as guardians of the forest, which symbolically takes care of the water that flows downhill.

What is needed to trickle down from the highland is not further zoning rules or regulations, but a reformation of attitude. The project proposed is a Slow Tourism School that guards the way capital translates into values.

Many private hotel owners have started initiatives to guard the growth of highlands by ensuring diverse economies and trash management. NGOs and outsiders also have participated. Working with this social commitment, the project proposes a model of education initiated and funded by the four guardians of the forest, with NGOs and private companies as lesser stakeholders.

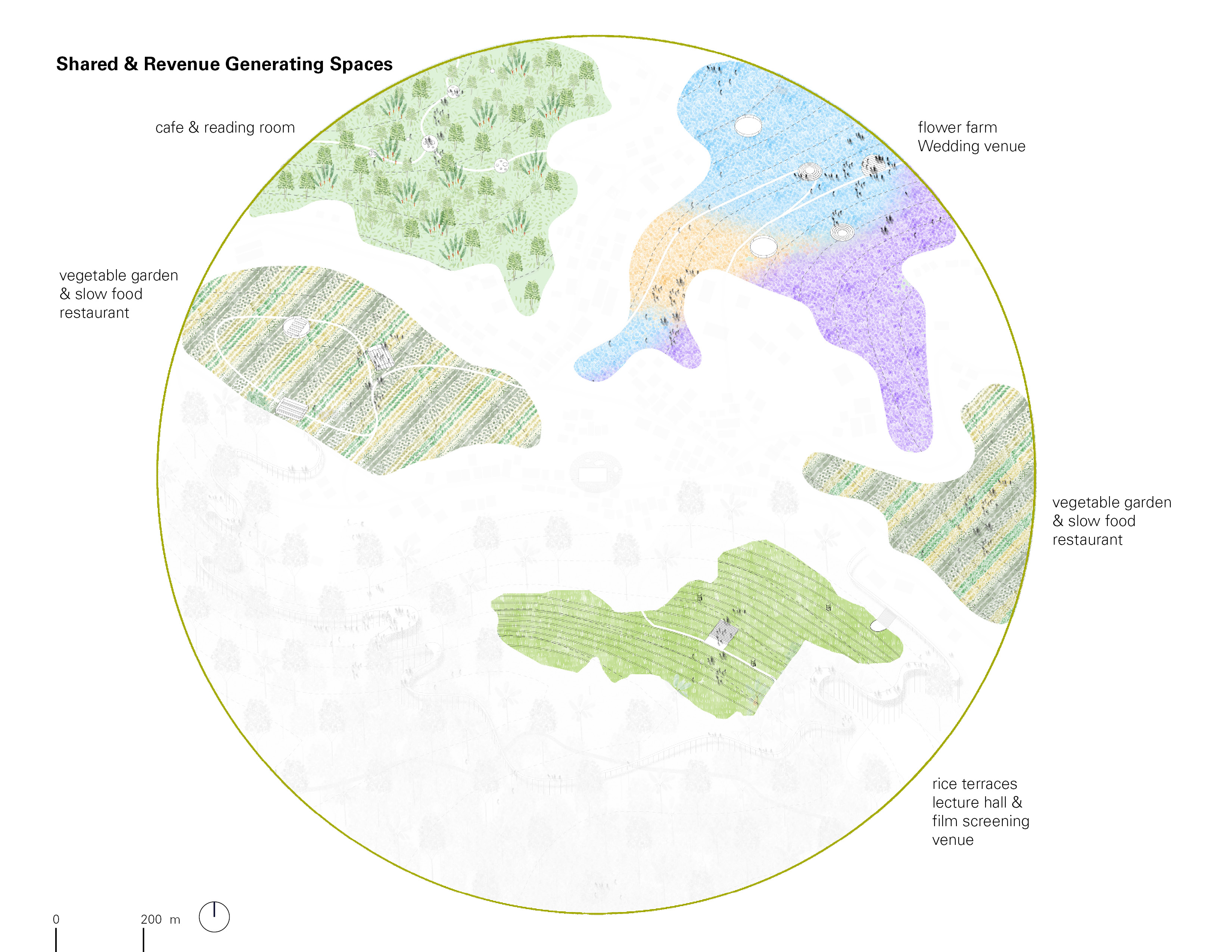

Located at the start and end of the Ritual Route is a temple. The project site encapsulates the temple, proposing area within it to become an institution consisting of sanctuary and slow tourism school. Within this zone, strict environmental principles are applied, such as the prohibition of plastic bags, chemical additives, and GMO. The sanctuary is a communally tended farm that brings back the diversity of species in the past as well as new ones, such as: coffee, rice, flowers, herbs, vegetables, and fruits. Within this sanctuary is a hospitality school that brings together locals and tourists into a shared learn and leisure experience.

Located at the start and end of the Ritual Route is a temple. The project site encapsulates the temple, proposing area within it to become an institution consisting of sanctuary and slow tourism school. Within this zone, strict environmental principles are applied, such as the prohibition of plastic bags, chemical additives, and GMO. The sanctuary is a communally tended farm that brings back the diversity of species in the past as well as new ones, such as: coffee, rice, flowers, herbs, vegetables, and fruits. Within this sanctuary is a hospitality school that brings together locals and tourists into a shared learn and leisure experience.

At the cloves picker path, a series of elevated walkways allow people to get close to the cloves tree, smelling the fragrant cloves flowers. The platform is elevated high and is made of minimal material to ensure sunlight penetration for other species that grow beneath. Whether seasonal clove pickers or mass tourism, the platform is big enough to accommodate flows of people.

Revenue generating spaces can be found within other parts of the garden, such as rice terraces that functions as an outdoor lecture hall and film screening facility, flower farm that doubles as wedding venues, slow food restaurant and café found among the coffee plantations and vegetable gardens.

The highlands of Bali is the most fertile for all kinds of crops, making it one of places with the most biodiversity in North Bali.

In the 1980s, increased price of cloves to be used for tobacco industry create high value of cloves. Along with the failure of coffee in lower highlands, many farmers converted their rice fields, cocoa, coffee plantations, and spices such as vanilla into cloves and orange groves.

While the villages of highlands (the guardians of the forest) are financially prosperous and the economy and landscapes of cloves and coffee have brought a new kind of beauty and traditions, many are lamenting the change in attitude among villagers as proliferation of private hotels increase privacy among residents. At the same time, ecological biodiversity is threatened. For example, Cloves fruits and coffee beans are not consumable by birds, breaking the ecology chain and reducing biodiversity in the area.

Development has resulted in the intensive use of plastic products that pollute the environment, and subsequently their identity as guardians of the forest, which symbolically takes care of the water that flows downhill.

What is needed to trickle down from the highland is not further zoning rules or regulations, but a reformation of attitude. The project proposed is a Slow Tourism School that guards the way capital translates into values.

Many private hotel owners have started initiatives to guard the growth of highlands by ensuring diverse economies and trash management. NGOs and outsiders also have participated. Working with this social commitment, the project proposes a model of education initiated and funded by the four guardians of the forest, with NGOs and private companies as lesser stakeholders.

Located at the start and end of the Ritual Route is a temple. The project site encapsulates the temple, proposing area within it to become an institution consisting of sanctuary and slow tourism school. Within this zone, strict environmental principles are applied, such as the prohibition of plastic bags, chemical additives, and GMO. The sanctuary is a communally tended farm that brings back the diversity of species in the past as well as new ones, such as: coffee, rice, flowers, herbs, vegetables, and fruits. Within this sanctuary is a hospitality school that brings together locals and tourists into a shared learn and leisure experience.

Located at the start and end of the Ritual Route is a temple. The project site encapsulates the temple, proposing area within it to become an institution consisting of sanctuary and slow tourism school. Within this zone, strict environmental principles are applied, such as the prohibition of plastic bags, chemical additives, and GMO. The sanctuary is a communally tended farm that brings back the diversity of species in the past as well as new ones, such as: coffee, rice, flowers, herbs, vegetables, and fruits. Within this sanctuary is a hospitality school that brings together locals and tourists into a shared learn and leisure experience.

At the cloves picker path, a series of elevated walkways allow people to get close to the cloves tree, smelling the fragrant cloves flowers. The platform is elevated high and is made of minimal material to ensure sunlight penetration for other species that grow beneath. Whether seasonal clove pickers or mass tourism, the platform is big enough to accommodate flows of people.

Revenue generating spaces can be found within other parts of the garden, such as rice terraces that functions as an outdoor lecture hall and film screening facility, flower farm that doubles as wedding venues, slow food restaurant and café found among the coffee plantations and vegetable gardens.

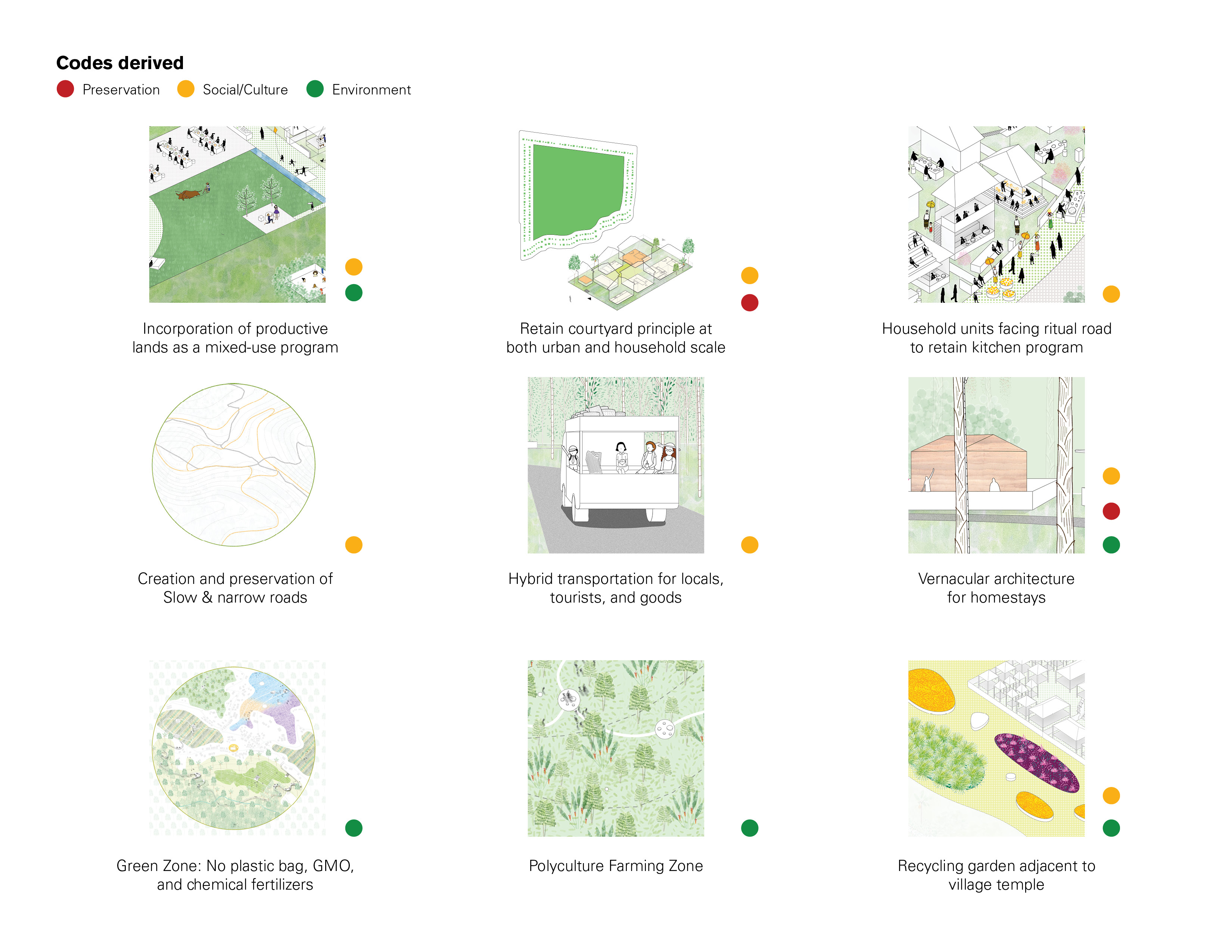

Codes Derived

The collection of projects along the first slow zone can be fleshed out to generate urban design guideline that becomes guiding principles for furthering development along the slow zone.

Through other ritual and cultural routes, many other sites can slowly become an alternative development trajectory that restore the balance among nature, people, and profit for Bali.

The collection of projects along the first slow zone can be fleshed out to generate urban design guideline that becomes guiding principles for furthering development along the slow zone.

Through other ritual and cultural routes, many other sites can slowly become an alternative development trajectory that restore the balance among nature, people, and profit for Bali.